Share

Voices of British Ballet

Coming soon

•

Launching soon - a new podcast bringing to life and celebrating the history of dance in Britain.

For more than 20 years the ballet dancer and teacher Patricia Linton has been recording interviews with the people who were there as the story of British dance unfolded across the twentieth century and beyond.

In this podcast you’ll hear from some famous names, as well those less well known, whose reflections help to build a rich picture of the art-form.

Subscribe to our podcast and find photos and extra content on our website, also launching soon.

More episodes

View all episodes

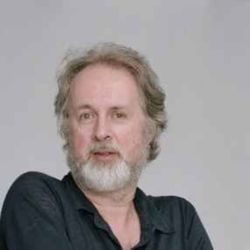

50. Richard Alston

26:02||Ep. 50The distinguished choreographer and director Richard Alston explains to Alastair Macaulay, how, as a teenager, he was entranced by watching ballet. After studying fine art, he began working on the Martha Graham technique with what became the London Contemporary Dance Theatre. He eventually found this too restricting and embraced the freer, less floor fixated approach of contemporary dance associated with Merce Cunningham. Alston goes on to discuss how his own choreography began, and how it developed in line with this expansion of his aesthetic. He speaks about his dealings with Cunningham and with the composer John Cage and also about his long and immensely fruitful creative partnership with Sue (Siobhan) Davies. The interview is also introduced by Alastair Macaulay.Richard Alston was born in October 1948 in Sussex. He is a British choreographer as well as having been artistic director for several dance companies. His education began at Eton College, followed by two years at Croydon School of Art. His passion for ballet was first sparked after attending performances by the Bolshoi Ballet and The Royal Ballet Touring Company, and also by Merce Cunningham and the Martha Graham Dance Company, which excited an interest in modern dance. As a result, he started attending classes with the Rambert School of Ballet, and in 1968 he became one of the London Contemporary Dance Theatre’s original students. After only three months there, he created his first work, Transit. In his third year at the School he organised a group of students to tour schools, colleges and universities demonstrating the Graham technique. After choreographing for London Contemporary Dance Theatre, he created an independent dance company, Strider, in 1972.In 1975, Alston travelled to New York to study primarily with Merce Cunningham at the Merce Cunningham Dance Studio. He returned to Europe two years later, working as an independent choreographer and teacher. In 1980, he was appointed resident choreographer for Ballet Rambert. He founded Second Stride with Siobhan Davies and Ian Spink in 1982, and in 1986 was appointed artistic director of Ballet Rambert, a post he held until 1992. To reflect the changing nature of the company and its work, in 1987 Ballet Rambert changed its name to become Rambert Dance Company. During his years with Rambert, Alston created 25 works for the company, as well as pieces for the Royal Danish Ballet and The Royal Ballet.After working in France and at the Aldeburgh Festival, in 1994 Alston became artistic director of The Place and he also formed Richard Alston Dance Company. A steady stream of over 50 dance works created by Alston over the next decades was interspersed with collaborations with the London Sinfonietta and Harrison Birtwistle in 1996, and several television productions, including The Rite of Spring, commissioned by the BBC for their Masterworks series in 2002. The Richard Alston Dance Company celebrated its tenth year with its first appearance in New York in 2004. In 2006 the company made its first full tour of North America, followed by further tours in 2009 and 2010. Alston created a new ballet, En Pointe, A Rugged Flourish, for New York Theatre Ballet in 2011. In March 2020, the Richard Alston Dance Company was wound up after a quarter of a century of critical acclaim., giving its last performance at Sadler’s Wells. Richard Alston received the De Valois Award for Outstanding Achievement in Dance at the Critics’ Circle National Dance Awards in 2009. He was appointed a CBE for services to dance in 2001, and was knighted in 2019.

49. Edward Watson

21:03||Ep. 49Over a long career, Edward Watson became one of The Royal Ballet’s greatest male principals, in the footsteps of Anthony Dowell and David Wall. He is particularly noted for his work in the ballets of Frederick Ashton and Kenneth MacMillan, and for creating many roles with contemporary choreographers. Here, in a conversation with Jane Burn recorded for Voices of British Ballet in 2007, he speaks disarmingly about his early days in The Royal Ballet before sharing some insights about portraying Crown Prince Rudolf in MacMillan’s Mayerling, a role for which he is particularly associated. The interview is introduced by Kenneth Olumuyiwa Tharp.Edward Watson was born in South London in 1976, and trained at The Royal Ballet School, first at the Lower School at White Lodge, and then at the Upper School in Barons Court. He graduated into The Royal Ballet in 1994 and was promoted to the rank of principal dancer in 2005. Watson’s pure classical technique, combined with a fine dramatic flair and sensitivity served him well in the works of Frederick Ashton, Kenneth MacMillan and Ninette de Valois herself, choreographers at the heart of the British tradition. He has himself been a major force in the continuation of that tradition.

48. Violetta Elvin

14:49||Ep. 48This episode is introduced by Dame Monica Mason. Violetta Elvin was one of Frederick Ashton’s favourite ballerinas. She was born Violetta Prokhorova in Russia. Here, in this interview with Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, Violetta traces her evacuation to Tashkent at the start of World War II and how she returned, via Kuibyshev, to Moscow to join the Bolshoi Ballet. Despite being warned by the authorities not to talk to foreigners, she married the British diplomat Harold Elvin and managed to come to London in 1946. Only weeks after her arrival she joined the Sadler’s Wells Ballet at Covent Garden and danced the “Blue Bird” pas de deux on the second night of their opening production of The Sleeping Beauty. The interview is introduced by Monica Mason.A dancer of rare beauty, Violetta Prokhorova was born in 1923. She trained at the Bolshoi Ballet School in Moscow and joined the Bolshoi Ballet in 1942, following her graduation performance, for which she was coached by Galina Ulanova. When Moscow was evacuated and the Bolshoi was scattered, she danced as a ballerina with the State Theatre of Tashkent. In 1944 she re-joined the Bolshoi in Kuibyshev, on the Volga, where she fell in love with a young Englishman, Harold Elvin. The Bolshoi returned to Moscow in early 1945. She danced with the Stanislavsky Ballet for a year, then married Elvin and obtained permission from Joseph Stalin to leave Russia.Once in London Violetta started training with Vera Volkova, where she was seen by Ninette de Valois and immediately offered a place in the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. She adored and was true to her Russian training, but with her intelligence and sensitivity she was able to fit in beautifully with the British repertoire. From the Black Queen in de Valois’ Checkmate, through all the classical ballerina roles to Roland Petit’s Ballabile in 1950, Violetta Elvin as she was now known, danced with exquisite vivacity, a hint of exoticism and always impeccable port de bras. Frederick Ashton created several roles for her, notably the Summer Fairy in Cinderella (1948), Lykanion in Daphnis and Chlöe (1951), and one of the seven ballerinas in Birthday Offering (1956). For a decade Violetta Elvin was a unique and irreplaceable member of the developing Sadler’s Wells Ballet. She went to live in Italy in 1956, and although she guested with several companies, including La Scala, Milan (where she performed alongside soprano Maria Callas) in 1952 and 1953, and briefly directed the Ballet of the Teatro San Carlo in Naples in 1985, she retired from ballet when her heart called her elsewhere.

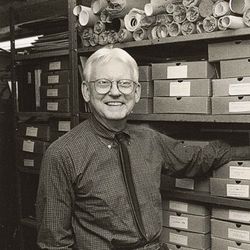

47. David Vaughan

22:17||Ep. 47David Vaughan – unparalleled writer on the choreography of Frederick Ashton – catches moments and movements from The Royal Ballet’s history. In this interview for Voices of British Ballet, which was recorded in New York, he talks to his friend and fellow dance writer Alastair Macaulay. The episode is also introduced by Alastair Macaulay.The archivist, historian and critic David Vaughan was born in London in 1924. He studied at Oxford University and only began dance training after that, in 1947. In 1950 he won a scholarship to study at the School of American Ballet, where he met Merce Cunningham, who was teaching there. Vaughan began studying with Cunningham from the mid 1950s. Later, in 1959, when Cunningham opened his own studio, Vaughan began performing various tasks for Cunningham and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, including co-ordinating the company’s six-month tour of Europe (with John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg) in 1964. Vaughan became the company’s official archivist in 1976, a post he held until 2012, when the company was disbanded following Cunningham’s death.In addition to writing and working for and with Cunningham, Vaughan was active in the theatre, film and dance worlds. He acted in off-Broadway productions, devised the choreography for Stanley Kubrick’s film Killer Kiss, and worked on the scripts for films about Cunningham and Cage, and about the choreographer Antony Tudor. Vaughan also appeared in several dance productions, including The Royal Ballet’s revival of Frederick Ashton’s A Wedding Bouquet. In 1988 he wrote an influential op-ed piece in The New York Times, criticising traditional ballet companies for not offering dancers of colour enough opportunities to perform.David Vaughan was a prolific and well-regarded writer on ballet and dance. His books included The Royal Ballet at Covent Garden (1976), Frederick Ashton and His Ballets (1977, revised edition 1999) and Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years (1996). He contributed frequently to the Dancing Times magazine, and with Mary Clarke he also edited and contributed to The Encyclopaedia of Ballet and Dance (1980). In 2015 David Vaughan received a Dance Magazine award. He died in New York City in 2017. Photograph courtesy of The Merce Cunningham Foundation

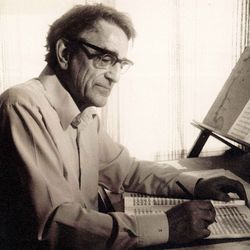

46. Ernest Tomlinson

16:23||Ep. 46In this no-nonsense, down-to-earth account of writing music for Northern Ballet Theatre’s production of Aladdin, choreographed by Laverne Meyer in 1974, composer Ernest Tomlinson talks to Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet. The interview is introduced by Stephen Johnson.Ernest Tomlinson was a British composer, well known for his contributions to light music and for founding The Library of Light Orchestral Music (which prevented the loss of 50,000 works released from the BBC’s archive and other collections). He wrote the music for the ballet Aladdin for Northern Ballet Theatre in 1974.Tomlinson was born in 1924, in Rawtenstall, Lancashire. His parents were musical, and he sang as a chorister at Manchester Cathedral. After a grammar school education, he studied at Manchester University and the Royal Manchester School of Music, with a break for war service in the RAF. He moved to London after graduation in 1947, working first for music publishers. In 1955, after some of his compositions had been performed by the BBC, he formed his own orchestra – the Ernest Tomlinson Light Orchestra – and set out on a highly successful freelance career as a prolific composer, conductor and director of choirs and orchestras. He was particularly concerned to counter the notion of a strict division between art music and popular music. His own Sinfonia 62 was written for jazz band and symphony orchestra, while his Symphony 65 was performed at festivals in London and Munich and in the Soviet Union in 1966, where it was the first symphonic jazz to be heard there. In 1975, Tomlinson won his second Ivor Novello Award for his ballet, Aladdin. Among many other professional appointments, he was the chairman of the Light Music Society from 1966 until 2009. Ernest Tomlinson was appointed an MBE for his services to music in 2012.

45. Patrick Harding-Irmer

20:42||Ep. 45Here is Patrick Harding-Irmer proving that it is never too late to start dancing. He says, in this interview with Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, he only began to take dance classes at the age of 24 but was soon working in dance commercially. In 1972, inspired by a visit to Australia by Nederlands Dans Theater, he came to Europe, where he fell under the spell of the Martha Graham technique and the teaching of Robert Cohan at London Contemporary Dance Theatre (LCDT). After nine months performing with the X Group, he joined the main LCDT, going on the be voted Best Contemporary Dancer in Europe in 1985. This interview was recorded in Sydney, Australia, in 2006 and is introduced by Kenneth Olumuyiwa Tharp.Patrick Harding-Irmer was born in Munich in 1945, where his Australian mother had been working in dance and choreography. After World War Two, she and he returned to Australia. In 1964 he represented Australia in the World Surfing Championships, and then began to study arts at Sydney University. At the age of 24 he began to take dance classes and to dance commercially. In 1972, inspired by a performance by Nederlands Dans Theater on tour in Australia, he travelled to Europe and began studying at London Contemporary Dance School, specialising in Martha Graham technique. That same year he joined the X Group of the London Contemporary Dance Theatre (LCDT), which included five dancers who toured the UK and abroad, demonstrating and teaching Graham technique. In 1973, after nine months with the X Group, Harding-Irmer joined the main company of LCDT. In 1985 he was voted Best Contemporary Dancer in Europe. He returned to Australia in 1990, and has subsequently taught, and also worked with Australian Dance Artists, a group of mature performers dancing their own creations in different settings.

44. Marcia Haydée

17:28||Ep. 44In April 2017, Marcia Haydée was in Stuttgart for a week to celebrate her 80th birthday. Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, knew this was her only opportunity to see Haydée in Europe, so she telephoned Stuttgart Ballet to see if she could interview her. Patricia takes up the story in her own words: “They listened to my request, and, in perfect English, said they would ask Miss Haydée. With a full schedule of rehearsals all week, Marcia said she was free on Thursday from 3.30pm to 4.30pm. She didn’t know me at all, but it was enough for her to know how much I loved Kenneth MacMillan’s ballet, Song of the Earth. So, I jumped on a plane…This is the extraordinary Marcia Haydée…”In the interview Haydée explains how she was aware of both John Cranko and Kenneth MacMillan as a student at the Sadler’s Wells (now Royal) Ballet School, without suspecting her later close involvement with both men. In working with them, Cranko came to appreciate her melding of a Russian and a British approach to dancing; MacMillan was demanding and uncompromising, but she always strove to fulfil his requirements. She speaks revealingly about working in Stuttgart with Cranko on Onegin and with MacMillan on Song of the Earth and suggests that in those days and in those works, dancers took things at a speed and with risks that today’s dancers, for all their qualities, do not attempt to emulate. The interview is introduced by Dame Monica Mason.Marcia Haydée is a Brazilian-born ballerina, choreographer and company director. She was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1937, and after studying in Brazil, came to the Sadler’s Wells (now Royal) Ballet School in London in 1954, joining the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas in Monaco in 1957. Haydée joined the Stuttgart Ballet in 1961 and was named prima ballerina the following year by the company’s director and choreographer, John Cranko. Their relationship – her dancing, his choreography – was to become the foundation of Stuttgart Ballet’s international reputation in works such as Onegin, Romeo and Juliet and The Taming of the Shrew, among many others. She also worked closely withKenneth MacMillan on works such as Las Hermanas, Miss Julie and, above all, his Song of the Earth and Requiem. In 1976, she became director of the Stuttgart Ballet, a position she held until 1996. During her dancing career she performed as a guest artist for notable ballet companies throughout the world. From 1992 until 1996 Haydée directed the Ballet de Santiago de Chile, and again from 2003 until 2004. Since retiring from performing she has pursued a career as a choreographer, teacher and coach, and she also stages many ballets.The episode photograph shows John Cranko in rehearsal with Marcia Haydée and Bernd Berg, 1962. Photo: Hannes Kilian, courtesy Stuttgart Ballet

43. Deborah Macmillan

23:54||Ep. 43Deborah MacMillan, who talks to former Royal Ballet principal Bruce Sansom, is not afraid to speak her mind. Here she variously both endorses and explodes myths. Apart from anything else, these ten minutes should give hope to anyone who suffers from depression – nothing is impossible. Through the gloom of life, both within and without, her husband, the choreographer Kenneth MacMillan, went on creating ballets that have given thousands of dancers around the world endless challenges and insights, let alone audiences. For all his breaking of moulds and pushing at frontiers, MacMillan’s absolute belief in the traditions of classical ballet is never far away. As well as being a choreographer, MacMillan was also director of The Royal Ballet from 1970 until 1977.The interview is introduced by Jennifer Jackson.Deborah MacMillan is the custodian of the ballets choreographed by her late husband, Sir Kenneth MacMillan, supervising productions of his works all over the world. Deborah Williams, as she then was, was born in Queensland, Australia, in 1944, and educated in Sydney. She studied paining and sculpture at the National Art School before moving to London in 1970, marrying Kenneth in 1974. She has designed ballets for both stage and television, as well as making numerous contributions to Royal Ballet productions, including the production realisation for the major revival of Anastasia in 1996, production and setting for a condensed version of Isadora in 2009 and costume designer for a revival of Triad in 2001. In 1984, Deborah returned to painting full-time and her work is represented in private collections both in the UK and the USA.From 1993 until 1996, Deborah was a member of the Royal Opera House Board, and in 1996 was chair of The Friends of Covent Garden. She has served as a member of the Arts Council of England from 1996 until 1998, when she chaired the dance panel. She has also been a trustee of American Ballet Theatre and a member of the National Committee of Houston Ballet. She became Lady MacMillan when her husband was knighted for his services to dance in 1983

42. Romayne Grigorova

17:51||Ep. 42Romayne Grigorova has had a long, distinguished career in ballet and the theatre. Here, in conversation with Patricia Linton, founder and director of Voices of British Ballet, she focuses on her early years, much of which was coloured by World War Two. In 1943, after training at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School, she worked with the Sadler’s Wells Opera on The Bartered Bride in London during the Blitz and on tour. In 1945 she travelled to Germany with the opera under the auspices of ENSA. She then joined Ballet Rambert, and went to Germany again, to Berlin, where she delivered food parcels to a German singer and her family in the Russian zone, and scissors to Lotte Reiniger, a famous German film director and pioneer of silhouette animation. Romayne Grigorova also speaks of her dealings with Marie Rambert and Andrée Howard, joining Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet in 1951 and touring to North America.The interview was recorded in 2003, and is introduced by Monica Mason who spoke to Natalie Steed before Romayne's death in July 2025.Romayne Grigorova was born in Sandwich, Kent, in 1927. She studied under Vera Volkova, Ninette de Valois, George Goncharov and Ailne Philips. Her first appearance on the professional stage was in 1942. In 1943, after training at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School for a further year, she danced in ballets with the Sadler’s Wells Opera in this country and, in 1945, on tour in Germany under ENSA. She joined Ballet Rambert in 1946 and then danced with the Anglo-Polish and Metropolitan Ballets until 1947, when the latter folded.Grigorova then worked in the commercial theatre until 1951, including performing in three pantomimes, before joining Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet, where she remained until 1955. She was ballet mistress for the stage musical Can-Can in 1955, and for the St Gallen Ballet in 1956. In 1957 she became ballet mistress for the Opera Ballet at the Royal Opera House, for whom she choreographed many ballets. She retired from this post in 1992 but continued to teach on a freelance basis. She performed small character roles with The Royal Ballet at Covent Garden, many of which had been created for her, such as Lady Montague in Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet and The Housekeeper in Peter Wright’s The Nutcracker. Romayne Grigorova was appointed an MBE for her services to dance in 2017. She died in July 2025.Photo by Donald Southern courtesy of The Royal Ballet