Share

The Business of Fashion Podcast

What Happens When It’s Too Hot to Make Fashion?

Many of fashion’s largest manufacturing hubs, particularly in South and Southeast Asia, are increasingly at risk of dangerous, record-breaking heatwaves. As extreme heat becomes more frequent, more intense and longer-lasting, what is the cost to industry and how will we adapt to the growing climate risks?

Senior correspondent, Sheena Butler-Young and executive editor, Brian Baskin sat down with BoF sustainability correspondent Sarah Kent to understand what rising global temperatures means for the future of garment production.

“We have to assume that it’s the new norm and or at least a new baseline. It’s not like every year will necessarily be as bad, but consistently over time, the expectation is things are going to get hotter for longer,” says Kent. “We both have to take steps to mitigate and prevent things getting worse, and we have to accept that we have not done enough to stop things getting this bad - and so we have to adapt as well.”

Key Insights:

- Extreme heat leads to productivity problems, including increased instances of illness and malfunctioning machinery — even air conditioning units. The reason this isn’t surfacing as a significant supply chain issue is that it occurs in short, sharp bursts. “The supply chain is flexible enough and sophisticated enough that it can be papered over for the moment, particularly at a time when demand is not at its peak,” shared Kent. “Not all factories are working at full capacity all the time, so if your productivity isn’t 100% you can manage that for a few days or a week.”

- When it comes to working conditions in garment factories, climate also tends to take a backseat, both for manufacturers and, often, the workers themselves. “The biggest issue for a worker is going to be okay, I’m not earning enough to feed my family, my job isn’t secure, and then it’s really hot and that’s making it worse,” Kent recalled hearing from union representatives in Bangladesh.

- Whilst brands understand the interconnectivity between their emissions and supply chain issues, the drive to produce what consumers want as swiftly and cheaply as possible doesn’t leave much room for manufacturers to prioritise investments to improve their environmental footprint or adapt their factories to be more resilient to climate extremes. “We’re going to need to raise the prices in order to do that. That becomes a very tricky conversation very quickly,” says Sarah. “The disconnect is between the delightful picture of peace, love, Kumbaya, green planet that the industry would like to suggest that it is gunning for, whilst at the same time paying prices that in no way support that.”

Additional Resources:

More episodes

View all episodes

Tariffs Are Down, But Uncertainty Is Back

18:43|Nearly a year after President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs sent shockwaves through the fashion industry, the Supreme Court ruled he did not have authority to impose the sweeping levies. For an industry that imports billions of dollars in clothing, footwear and accessories into the US each year, the decision initially felt like relief. But that optimism narrowed almost immediately as new tariffs were introduced at 10 percent, with Trump indicating they could be raised to 15 percent over the weekend.Key Insights:While a drop to a 15 percent tariff technically represents a rate reduction, the sudden policy reversal has plunged the industry back into a state of operational paralysis. Executives are struggling to form long-term strategies when the foundational rules of global trade shift from week to week. “The problem isn’t even the difference in the rate of tariffs,” Chen explains. “It’s that the uncertainty makes decisions so much harder than if we knew exactly what that rate was going to be, even if it was higher than before.” This volatility forces companies to make reactive, shipment-by-shipment choices rather than fortifying their businesses for the future.The sheer scale of the disruption means that import duties can no longer be managed as a siloed logistical issue. Navigating the changing rules requires constant, cross-departmental negotiation to align product adjustments with consumer messaging. As Bain notes, “In the past, with something like this you would talk to your supply chain manager and come up with a plan with them. Now, you get everyone in the C-suite together into a war room … it’s just constant negotiation within your company and with your consumers.” Despite social media chatter suggesting that brands and consumers are owed money for the now-illegal tariffs, the reality of recouping those funds involves a looming legal nightmare. The government is expected to aggressively fight payback efforts by demanding extensive paperwork or proof that costs were not passed onto shoppers. “Refunds are a possibility, but it's not going to be a simple process,” Bain says. “It's not like returning your e-commerce order online where you fill out a form and you get a bunch of money back.”Fashion has experienced significant sticker shock over the past few years, but brands that successfully raised prices without losing consumer demand are unlikely to surrender those gains now. If the cost of production decreases under the new tariff structure, powerful labels will likely absorb the difference to improve their margins. “I think it's a possibility that some brands and retailers will lower their prices, likely in the form of discounting, rather than lowering retail prices,” Chen says.Additional Resources:The Supreme Court’s Tariff Ruling: What Fashion Needs to Know | BoF US Supreme Court Overturns Trump’s Emergency Tariffs | BoF Will Prices Come Down With Trump’s Tariffs? It’s Complicated | BoF

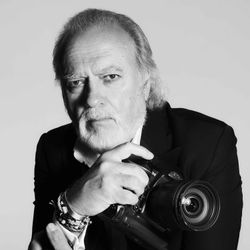

London’s Premier Party Photographer on the Art of Working a Room

55:47|If you’ve been to a major party in London, Paris or Los Angeles, chances are that Dave Benett was there too. For nearly four decades, Benett has been a constant presence, documenting the evolution of celebrity, society and style in all the spaces and places where culture is happening. From concerts with Madonna and Prince to after-parties with Princess Diana and the rise of fashion as a pillar of culture, Benett has seen it all and become an expert at the art of working a room.“Journalists can miss something [and] be told about it. Photographers can’t,” he says. “Whatever you’re doing, you’ve got to make sure your eyes are everywhere.”This week on The BoF Podcast, Benett joins Amed to talk about what it really takes to cover an event, how party photography has changed in the era of smartphones and Instagram, and why relationships — not just access — are everything.Now he is launching the Dave Benett Agency — a boutique model designed to protect quality, mentor a new generation of photographers and adapt to an era where everyone has a camera, but very few know where to stand.Key Insights: Born in Mauritius in 1958, Bennett moved to the UK as a child and by his late-teens was honing his photography skills at the Daily Mirror and Thames TV, covering riots and crime before pivoting to the social scene. He witnessed the cultural shift where fashion merged with music and celebrity: “We started to see it when Kate Moss, Naomi [Campbell], Vivienne Westwood and the The Fashion Awards all started to happen.” Bennett operates as what he calls a "society photographer," a role built on mutual respect and long-term relationships. He explains, "we were recording what society was doing. We photographed the royals but when they came into our world and that relationship really did make a difference.” This trust was exemplified by his interactions with Princess Diana at private events. “I would just photograph her arriving and meeting the host and then she could go off and chat to all her friends. She felt safe ... and it really paid off for us as the doors closed later on."While the digital revolution has democratised image-taking, Dave argues that there is a distinct gap between a personal snapshot and a professional photograph. He acknowledges that "the power of the individual has increased massively," but maintains that the industry still relies on a specific editorial eye. "The good thing for me is that they still need what we do, because we're shooting for a client ... and there's a skill that comes with that — how you take a photo, what you're looking for in the photo. When you've got people with their own cameras, their own phones, taking their own pictures, they practically have only one use — for themselves."Benett describes event photography as a tactical exercise, mapping arrivals, tracking key players and staying on his feet for hours. To capture the right moments, he explains: "You work out exactly where you need to be for the initial arrival or where they come, then you work the room as and when new people arrive. You can actually spend four hours just campaigning the room, just making sure you're in the right place at the right time." Additional Resources: The Return of Old-School Celebrity Campaigns | BoFHow Celebrity Image-Makers Capitalise on the Red Carpet | BoF .

How Dior and Chanel Are Winning Back Aspirational Shoppers

19:44|After raising prices aggressively during the post-pandemic boom, luxury brands are now confronting slower growth and a shrinking aspirational customer base. According to Bernstein, average luxury price hikes reached 36 percent between 2020 and 2023, with Dior and Chanel raising prices by 51 percent and 59 percent, respectively. Now, as Bain estimates that more than 50 million aspirational shoppers have left the category, both houses are adjusting their pricing architecture and product mix in an attempt to rebuild volume without sacrificing exclusivity.BoF reporter Joan Kennedy joins The Debrief to unpack how Dior and Chanel are recalibrating pricing and product strategy to win back aspirational shoppers. Key Insights:Dior and Chanel are among the brands that leaned hardest into post-pandemic price increases, prioritising margin expansion and high-net-worth clients. That strategy helped fuel growth at the time, but it has also intensified the industry’s current reckoning. “Pricing has really emerged as this key concern,” Kennedy says. “At Dior and Chanel, prices rose 51 per cent and 59 per cent, respectively.” Products that once served as entry points are increasingly out of reach for aspirational shoppers: “The Chanel medium flap has nearly doubled in price since 2019,” she says.To pull aspirational shoppers back into stores, Dior and Chanel are rebuilding the lower end of their offer – from small leather goods and accessories to playful add-ons. As Kennedy puts it, “brands have been introducing these fun little whimsical items at the bottom, which have a good psychological effect on all shoppers.” And even when the ticket doesn’t shift, brands are trying to make the value proposition feel stronger through newness and storytelling: “maybe the price isn't changing, but it’s trying to hammer home that there's a little bit more value … and really ride the momentum brought by these new creative directors.”Even if excitement around creative directors Jonathan Anderson and Matthieu Blazy reignites interest, the economic backdrop may limit how far that enthusiasm translates into sales. “It’s definitely a big open-ended question – how much of this is a problem with desire versus ability to purchase?” Kennedy says. “Maybe a lot of these shoppers do want these products and are really excited by them, but just don’t have the ability.” In that sense, the reset is only partially in luxury’s control. Products can restore aspiration, but macro conditions ultimately determine movement.Additional Resources:How Dior and Chanel Are Tackling Fashion’s Pricing Problem | BoF The Great Fashion Reset | Can Designer Revamps Save Fashion? | BoF Ready for Relaunch? Jonathan Anderson’s Dior Challenge | BoF

Ib Kamara: ‘Europe Is Not the Centre of Everything. Where You Come From Matters.’

27:22|From a childhood in Sierra Leone to navigating London as a teenage immigrant, Ib Kamara traces the cultural shocks that shaped his creative identity. He recounts hiding his artistic ambitions while studying science, breaking through with a Beyoncé commission in his early 20s, redefining Dazed as a global publication and ultimately stepping into the role of art and image director at Off-White after the death of Virgil Abloh.BoF founder Imran Amed sat down with Ib Kamara in Abu Dhabi during the launch of T Magazine MENA. The conversation spans authorship, responsibility, design versus styling and why young creatives today must reject Eurocentric hierarchies and build with their peers. Key Insights: Kamara describes his move from Sierra Leone to London at 15 as both destabilising and transformative. Raised in a culture where authority was not questioned, he suddenly had to become outspoken and self-defined. That rupture, he says, forged his identity. “London was definitely a culture shock, but also the best shock that could have ever happened to me,” he reflects. “I think I needed that shock and that tension to be Ibrahim right now.”Kamara’s entry into fashion wasn’t through formal design training but through images. Growing up in Sierra Leone, he consumed discarded European magazines, absorbing visual storytelling. “I loved images and I was fascinated by how people put things together,” he explains. “I understood images quicker than design because there was no sort of a design school or artistic design language. You take what you’re given.” That instinct for narrative over product shaped his early styling career and later informed his editorial leadership at Dazed.Kamara approached Dazed as an editor with an immigrant’s vantage point and a global-first mandate, pushing the title beyond its London bias to reflect the way culture now moves online. “I realised London is so diverse and we all come from the most incredible places in the world. It will make sense for us to reflect that,” he says. In practice, that meant building an editorial agenda shaped by the same cross-border conversation happening among young audiences. “We’re at an age where the kids are all talking online, everyone is sharing and collaborating,” he continues. “So I set out to make a magazine that was global, has a sense of culture, has empathy and is brave enough to do stories that could potentially get me fired a couple of times … It’s a reflection of where I come from.”Taking the creative helm at Off-White after Virgil Abloh’s passing was not a straightforward decision. Kamara speaks candidly about fear, self-doubt and the weight of legacy. “It was not the easiest decision for me to make because no one can really fulfil someone else’s shoes,” he says. “There’s only one Virgil.” Ultimately, he chose growth over comfort: “I don’t think you can live life like that. I think you have to take a chance.” In moving from stylist to designer, he also discovered a harder truth about authorship: “With design you can’t cheat. I think with styling you can cheat in a picture … but design is respect – it’s a craft.”For young creatives navigating today’s instability, Kamara offers a clear directive to decentralise Europe and build locally with conviction. “Europe is not the centre of everything,” he says. “Where you come from matters. And taste is not subjective to one part of the world. It's a global taste.” His guidance is rooted in consistency and community: “Create with your people, bring your people up … There’s nothing more beautiful when you’re at a table and you’ve known these people for 20 years.” And above all, kindness: “Be kind as well. Be nice a little bit, if you can, please. We don’t need more monsters in the industry.”Additional Resources:Ibrahim Kamara | BoF 500 | The People Shaping the Global Fashion Industry How I Became… Senior Fashion Editor-at-Large of i-D Magazine | BoF Ib Kamara: Fashion’s Favourite Renaissance Man | BoF

How Fashion Brands Are Winning the Winter Olympics

23:50|While the Olympics remain one of the world’s biggest sporting stages, they are also one of the most tightly controlled marketing environments. Rules limit how sponsors can interact with athletes and advertise during the Games. As a result, fashion and sportswear brands are finding alternative ways to capitalise on the moment, from outfitting national teams and launching capsule collections to sending squads of influencers to experience the Games.BoF correspondents Haley Crawford and Mike Sykes join Sheena Butler-Young and Brian Baskin on The Debrief to unpack how the winterwear boom is reshaping the Olympic marketing playbook. Key Insights:Musician Bad Bunny’s choice of Zara for his Super Bowl halftime show outfit crystallises a broader tension in fashion marketing: the balance between cultural relevance and commercial perception. Whilst Sykes acknowledged the pushback from critics who found the use of a fast-fashion Spanish brand on such a global platform surprising, he also notes the strategic logic. “This performance is supposed to be about inclusivity, and part of that is accessibility and affordable products. And plus, Zara is also a Spanish brand... It makes more sense considering the cultural magnitude of the performance,” Sykes says.Crawford argues the Games are no longer just about logo placement on performance gear, but a broader spotlight on winter fashion as a growing category. “We've seen that consumers are interested, not only from a performance perspective, but also from a fashion-forward perspective, in having gear that's equally stylish as it is performance driven on the slopes,” she says. But Olympic marketing comes with strict limitations. As Crawford explains, official sponsors can use Olympic branding, but others must tread carefully. For non-sponsors like Canadian label Roots, that means linguistic gymnastics: using phrases like “rooting for Canada” without explicitly referencing the Games.With broadcast advertising and official branding tightly controlled, being visibly present at the Games can be the most direct route to global reach. Sykes points to Adidas’ scale: “We’ve seen a bunch of brands like Adidas…that launched this 700-piece collection.” Even if it is not a traditional campaign, the visibility is enormous. “Just to have your logos on some of these athletes as they perform, while millions of people are watching across the globe, that is the sort of marquee way we’re seeing brands participate,” he says.As leagues and federations try to expand their audiences, fashion-forward fan wear has become a strategic priority. Crawford says Off Season’s approach to Team USA illustrates the shift: rather than just jerseys, brands are creating “wearable jackets and sweaters and things that fans can actually wear in their day-to-day.” Sykes sees the trend as part of a wider evolution across sport. Off Season’s product “reminds me of what the Starter jackets used to be in the 90s,” he says, predicting that more brands will build momentum by “taking team logos and putting them on unique products that aren't just a jersey.”While the Olympic window is tightly controlled, brands often see their biggest opportunities once the closing ceremony ends. Crawford points to the Paris Olympics breakout star Ilona Maher, who “popped off for creating all this viral behind-the-scenes content in the Olympic village,” then landed deals with Maybelline and Paula’s Choice. For fashion, Suni Lee is a recent template. After Paris, she started campaigns for LoveShackFancy and Victoria’s Secret Pink and attended the CFDA Awards with a designer partner. “She really built this whole other part of her public persona,” Crawford says – showing how medals and momentum can translate into longer-term brand equity.Additional Resources:How the Winterwear Boom Reshaped Fashion’s Olympic Playbook | BoF Which Winter Olympians Will Score Beauty Deals? | BoF

Ask Imran Anything: Luxury’s Flop Era, Global Market Dynamics, Fashion Careers and more

25:52|In this Ask Me Anything episode, Imran Amed answers questions submitted by listeners from around the world, spanning luxury’s current downturn, the collapse of major wholesale platforms, the realities facing emerging designers, and how global growth narratives in India and Africa are often misunderstood. The conversation later zooms out to hear Amed’s advice on education and training, fashion journalism, and the skills needed to build a lasting career in an industry undergoing structural change.Key Insights: Amed frames the current downturn in luxury as fundamentally different from previous crises, arguing that this moment is rooted in structural choices made by the industry itself. Years of overexpansion, inflated pricing and relentless product drops have weakened trust and eroded meaning, leaving consumers disengaged. “The moment we’re in now feels different to me, because what’s happening is coming from inside the industry,” he says, pointing to oversaturation and a breakdown in perceived value. Despite the democratisation promised by direct-to-consumer channels, Amed believes this is one of the most difficult environments in decades for independent brands to gain traction. The collapse of key multi-brand platforms, combined with slow payment terms and intense competition, has made growth and cashflow management increasingly precarious. Yet, he sees opportunity for designers offering clarity and restraint where big brands have overreached. Smaller brands can compete by offering real value — “beautifully designed, high-quality products…that come from a sense of quality,” he explains, positioning scarcity and sensible pricing as advantages rather than constraints.Amed cautions against simplistic narratives that frame India or Africa as the next, immediate growth engines for Western luxury. In India’s case, he argues that expectations often ignore deep-rooted cultural and economic realities. “India already has a luxury industry that goes back hundreds of years,” he says, pointing to longstanding traditions in jewellery, tailoring and textiles that continue to shape consumer behaviour today. Africa, meanwhile, represents enormous long-term potential, driven by demographics, creativity and cultural influence — but much of luxury’s engagement still happens outside the continent. “Africa has more than a billion people and the fastest-growing population in the world — there’s no doubt that’s a huge future opportunity,” he says.Amed rejects the idea that there is a single route into fashion, but he is clear that success today demands a broader skill set than creativity alone. For designers, technical understanding and business literacy are increasingly essential if you want to build something sustainable. For journalists, Amed argues that a “point of view is the single most important thing in fashion journalism today.” He summarises: “ The one thing that’s true, whether you go to journalism school or not, is you just need to practice. If you’re a writer, you need to write every day. If you're a creator, you need to create every day. The more you write, the more you create, the more you’ll develop your own voice and the more you’ll feel confident in what you’re doing.”Additional Resources:Why India Will Not Be The Next China for Luxury | The BoF Podcast The Emerging Designers Pushing Fashion Forward | BoFThe Great Fashion Reset: Can New Designers Still Build a Business? | The Debrief | BoF

The New Rules for Influencer Marketing

24:49|Influencer marketing in 2026 is a different beast. Once dominated by follower counts and splashy sponsored posts, the sector is now shaped by richer performance data, new monetisation models and growing consumer scepticism toward overt selling. As BoF publishes a new case study on the creator economy, Pearl joins hosts Sheena Butler-Young and Brian Baskin to unpack how creators and brands are adapting to a more disciplined, competitive and AI-saturated landscape.Key Insights:One of the most profound shifts in influencer marketing is how success is measured. Where follower size once acted as a blunt proxy for reach, brands now have access to granular data that shows who actually drives traffic and sales. Pointing to platforms like ShopMy and LTK that allow brands to see “exactly what creators were driving sales for them,” Pearl says that visibility has reshaped spending decisions. She explains: “Having more data has totally changed the game. It really is incredibly varied today and there is no one baseline KPI. It’s really just about what are your goals and who’s the best to help you achieve that.”As consumers grow wary of constant selling, trust has emerged as the defining asset creators bring to brands. “Trust is the most important thing,” Pearl says. “If you don’t have your audience’s trust, nothing else matters.” What brands are really buying is not visibility, but a relationship. “What a creator really brings to the table is not necessarily the size of their following; it’s that relationship they have with their audience,” Pearl explains.As the sector professionalises, creators are actively reducing their dependence on single revenue streams. Affiliate marketing, subscriptions and owned platforms are increasingly central to sustainable creator businesses. “Affiliate marketing really provides that base foundational income that you can rely upon,” Pearl says. Substack, meanwhile, offers something brands cannot. She explains: “It brings back some of that intimacy and community that they felt was missing in this TikTok/Instagram world.” This diversification also changes the power balance. “They don’t want to rely too much on one particular partnership,” Pearl says. The upshot is a creator economy that is less fragile – and less easily dictated by brand budgets.Pearl argues the relationship between brands and creators is moving from transactional campaigns to longer-term collaboration. As creators become central to marketing in fashion and beauty, brands are changing how they work with them – and what they ask them to do. Brands can no longer dictate terms “like they used to,” Pearl says, because creators are now “recognised as being a really important part of the marketing puzzle.” That recognition is also changing what brands value: “You’re not just hiring this person for their following… you hire them because they’re a creator. They create great content. They know how to engage an audience.”Additional Resources:From Hype to Discipline: The New World of Influencer Marketing | Case Study Why There Are So Many Influencer Collaborations Right Now | BoF How Creators Can Avoid Being Replaced by AI | BoF Examining 20 Years of Fashion’s Influencer Economy | The BoF Podcast

The Couture Season That Cut Through

55:10|Editor-at-large, Tim Blanks and editor-in-chief, Imran Amed are back from the Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2026 shows where the biggest moments of the week lived up to all the anticipation.Jonathan Anderson’s debut at Dior reframed couture as a six-month creative lab — a backbone that can feed the entire maison with technique, emotion and ideas. At Chanel, Matthieu Blazy stripped away the obvious codes to put construction, movement and the body first — the kind of couture you only fully understand up close. There was also Valentino’s “panorama” staging and Schiaparelli’s turbocharged push for spectacle — all playing out against a tougher luxury backdrop this year’“Something that struck me about this season is the energy that everybody was evoking,” Blanks says. “The words people used to describe their feelings — it was Jonathan talking about having a lot of anger he needed to get out, or Mathieu talking about nature, or Alessandro talking about fantasy and fashion, and then Daniel Roseberry talking about turbocharging Schiaparelli.”Key Insights: Departing from the codes of previous designers, Blanks was struck by how much of Anderson’s own sensibility made it onto the Dior runway, from Magdalene Odundo’s vase forms to historic textiles and witty, collectible accessories. “I felt like there was real synthesis … I think he showed some of the most beautiful things he’s ever shown, and some of the most joyful clothes.” Within 90 minutes of the show, the full collection was installed at Villa Dior for clients to handle and order, underscoring Anderson’s structured, end-to-end planning. As Amed notes, “He’s operational … he thinks about the way it all works together. That’s quite rare in a designer.”Mathieu Blazy pared Chanel back to construction and movement, dialling down overt couture signatures to foreground cut and daytime dressing. The result read as a wardrobe built on the body rather than surface effect, with exquisitely fine details – budgies perched on pocket anchors, bird-on-mushroom motifs, slingbacks with tiny avian heels – that reward close looking. The Grand Palais spectacle amplified the tension between intimacy and scale, but as Blanks notes, “it does underscore in a very graphic way that couture is the ultimate private pleasure.”Alessandro Michele’s Specula Mundi for Valentino revived the 19th-century Kaiserpanorama to slow the audience’s gaze and amplify detail. Reading from Alessandro’s letter, Blanks highlights: “We continue to work within this space not to fill an absence, but to preserve it. Only by accepting such a void, with no intention to fill it, can Valentino’s legacy remain what it has always been.” Another line reads: “There is no fantasy without beauty, and there is no freedom without beauty and fantasy.”A common thread this season is that designers are newly humbled by the expertise of the craft. “Everybody was talking about their ateliers, all these ready-to-wear designers being confronted with what a couture atelier is capable of,” Blanks says. After visiting Valentino, he notes: “There were five separate ateliers working on the clothes… I can’t thread a needle, but I got kind of palpitations walking through – it’s just so incredible, that kind of artistry.” Anderson himself calls Dior’s workrooms a “mini city” of ultra-specialists.Additional Resources:Couture Has Entered a New Era. What Does It Mean? | BoF Blazy’s Chanel Couture Was a Slam Dunk! | BoF Exclusive: How Jonathan Anderson Is ‘Rebooting’ Couture at Dior | BoF The Beating Heart of Haute Couture | BoF

Making Sense of Fashion’s Brutal Job Market

22:44|Across fashion, companies that once embraced remote or hybrid work are increasingly pushing employees back into the office, with some moving towards four or even five days a week. At the same time, competition for jobs, particularly at entry level, is intensifying amid layoffs, slower industry growth and the rise of AI. On this episode of The Debrief, senior correspondent Sheena Butler-Young and executive editor Brian Baskin are joined by BoF Careers’ Sophie Soar to unpack why the power balance has shifted back to employers, how different generations feel about being in the office, and what practical routes still exist for early-career talent trying to get a foot in the door. Key Insights:During COVID, companies found people could be “just as, and in some cases, more productive” at home – but that was when productivity meant output. Now, Butler-Young argues that employers are widening the definition: “Productivity should also include collaboration, morale, people being together… face time with leaders.” And with the labour market tightening following economic pressure, layoffs and AI taking some jobs, leaders have more leverage to enforce it. “In 2025 and now into 2026, it’s looking more like an employer’s market,” Butler-Young says.While some executives argue that in-person work improves collaboration and reduces errors, Butler-Young warns that motivations are not always benign. She points to a growing sense that mandates can act as a quiet form of workforce reduction. “One way you can get people to effectively fire themselves is to make them come to the office,” she says, noting that some companies may prefer attrition to public layoffs. She also cautions against copy-and-paste policies. “If you’re seeing productivity high and morale high at one to two days a week, you need to ask yourself, what am I hoping to accomplish if I move it to four or five?” Despite a difficult labour market, Soar stresses that fashion companies have not stopped hiring altogether. Instead, they are being more selective, particularly when it comes to junior roles that can be automated. "There definitely is a squeeze on the ones that are considered more rote work,” she says. “Those are the roles you could potentially automate or replace with AI.” However, some employers are still investing in early-career talent. “Those who are still hiring for entry-level roles recognise the benefit that that talent can bring,” Soar explains, pointing to diversity, long-term retention and fresh perspectives.Additional Resources:Fashion Is Done With Remote Work | BoF How to Get Ahead in Fashion’s Stagnant Job Market | BoFHow Fashion Brands Are Making Remote Work Permanent | BoF