Share

Babbage from The Economist

Babbage: How Elon Musk’s satellites could change warfare forever

SpaceX’s Starlink was designed to provide off-grid high-bandwidth internet access to civilians. But the mega-constellation of satellites has become more famous for its role in Ukraine. In 2022, it became vital to the country’s war effort, revealing the military potential of near-ubiquitous communications. Now, with more companies and countries piling in to build their own mega-constellations, a new space race is on.

Shashank Joshi,The Economist’s defence editor, and Tim Cross, our technology and society editor, examine how the satellites have saved Ukraine and changed warfare. Aaron Bateman of George Washington University explores the military history of satellite communications. And Herming Chiueh, Taiwan’s deputy minister for digital affairs, explains why the threat from China has led the island to pursue its own Starlink-like satellite system. Alok Jha hosts.

For full access to The Economist’s print, digital and audio editions subscribe at economist.com/podcastoffer and sign up for our weekly science newsletter at economist.com/simplyscience.

More episodes

View all episodes

How to think like a chess pro

34:36|How do the world’s best chess players operate? What does the game itself reveal about thinking and memory? In this episode, Jennifer Shahade explains how thinking like a chess champion can help you make better decisions in life.Guests and hosts:Jennifer Shahade, Woman Grandmaster and author of “Thinking Sideways”Alok Jha, host of “Babbage”You can watch Alok and Jennifer play their chess game here.Topics covered:ChessCognitive scienceArtificial intelligenceTranscripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+.For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

Can “world models” fix AI’s blind spots?

42:04|Modern artificial intelligence is seemingly unstoppable. But large language models have an undeniable blind spot: an incomplete understanding of physical reality and the laws of physics. Could “world models” be the solution—and how are AI labs building them?Guests and hosts:Alex Hern, AI writer at The EconomistYann LeCun, AI pioneer and executive chairman at AMI LabsShlomi Fruchter, research director at Google DeepMindCristóbal Valenzuela, CEO at Runway AIAlok Jha, host of “Babbage”Topics covered:Large language modelsWorld modelsGoogle's Project GenieTranscripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+.For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

NASA’s Artemis: humans are returning to the Moon

38:29|NASA’s much-delayed Artemis II mission is set to launch in early March. For the first time since 1972, astronauts will fly around the moon—if all goes well, that means humans could walk on the lunar surface once again in a subsequent mission. But, if China succeeds in its own ambitions, those astronauts might not be alone. A new Moon race has begun.Host: Alok Jha, The Economist’s science and technology editor. Guests: The Economist’s Tim Cross and Oliver Morton; and Teasel Muir-Harmony of the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum.For more on America’s Moon programme, listen to our podcast on the inception of NASA’s giant (and pointless) SLS rocket.Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+.For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

Jimmy Wales: Wikipedia’s founder on surviving AI

40:25|Wikipedia, a volunteer-written encyclopedia, has defied the odds to become one of the world's most popular—and trusted—websites. Today, the project is under threat from divisive politics and the rise of generative AI. But Jimmy Wales, Wikipedia’s resilient founder, argues that the encyclopedia—and the human values which underpin it—are more relevant than ever.Host: Alok Jha, The Economist’s science and technology editor. Guests: Andrew Palmer, host of The Economist’s “Boss Class” podcast; and Jimmy Wales, founder of Wikipedia and the author of “The Seven Rules of Trust: Why It Is Today's Most Essential Superpower”.Andrew’s new series of “Boss Class”, which explores how to master management in the age of AI, is out on January 29th.Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+.For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

Trailer: Boss Class Season 3

02:18|AI is changing how we work. It's turning us all into managers. Be a good one.The Economist’s management columnist, Andrew Palmer, takes on the bots in the third season of Boss Class. From cloning to coding, agents to entry-level jobs, he tackles the threat head on and figures out how to turn anxiety into opportunity. Along the way he meets bulls and bears and the people who can help you to master management in the age of AI.Full Season 3 out 29th January 2026.To listen to the full series, subscribe to Economist Podcasts+.https://subscribenow.economist.com/podcasts-plusIf you’re already a subscriber to The Economist, you have full access to all our shows as part of your subscription. For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

Custom cures: tailor-made drugs for rare diseases

42:27|A teenage girl in Britain recently received a custom-made drug to fix a fault in her genetic code. Doctors hope that it will treat her ultra-rare neurodegenerative condition. It is also part of a medical trial that could transform the way that customised medicines are made available to people who otherwise have no alternatives. Host: Alok Jha, The Economist’s science and technology editor. Guests: Natasha Loder, The Economist's health editor; Julia Vitarello of EveryONE medicines; Paul Gissen of UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health.Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+.For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

Lone dangers: the physical toll of social isolation

34:57|Loneliness and social isolation are connected to around 100 deaths every hour, according to the World Health Organisation. Feeling lonely has been linked to cardiovascular disease, neurological conditions and problems with the immune system. Developing better social connections could improve millions of peoples’ health, but doing so is not as simple as it sounds.Host: Alok Jha, The Economist’s science and technology editor. Guests: The Economist’s Ainslie Johnstone; Julianne Holt-Lunstad of Brigham Young University. Thanks to Patrick Abrahams, Helen Kingston and Caroline Blake in Frome, England. Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+.For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

Mark McCaughrean: the astronomer’s guide to the cosmos

38:44|Fancy taking a trip to outer space? Explore the most extraordinary corners of the universe with astronomer Mark McCaughrean as your tour guide. In this episode, he tells us about everything from the curious clouds and comets in our own solar system, to distant stellar nurseries and whether or not we should be worried that our galaxy, the Milky Way, is on a collision course with a neighbour, Andromeda.Host: Alok Jha, The Economist’s science and technology editor. Guest: Mark McCaughrean of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and the author of “111 Places in Space That You Must Not Miss”.Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+.For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

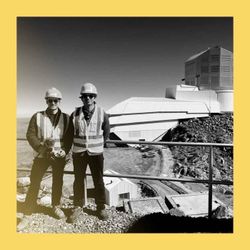

The discovery machine: a highlight from 2025

57:09|In the summer of 2025, we travelled to the Vera Rubin Observatory, a new telescope in Chile. This week, we’re revisiting that trip to the Andes Mountains, which showed how the Rubin Observatory’s upcoming decade-long sky survey hopes to uncover huge cosmological mysteries. In doing so, it is changing the way astronomy is practised.Host: Alok Jha, The Economist’s science and technology editor. Contributors: Victor Krabbendam, Stephanie Deppe, Leanne Guy, Yusra AlSayyad and William O’Mullane of the Vera Rubin Observatory. Listen to the full episodes here—part one and part two. Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+.For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.