Share

This Sustainable Life

499: What sets limits on pollution, part 2: some answers

The notes I read from for this episode:

I asked many questions on the last episode. The core ones were “why aren’t we switching to renewables and not polluting faster?” I know we can’t switch overnight, but what sets the pace? Do we know if the limits will go away, like we just need to build more factories, or maybe they won’t, like what led us to retract from supersonic flight? It worked in some ways, but not enough. A mix of social, business, engineering, and physics issues pulled us back.

How much farther can advances go? Can we expect as great advances as the 747 compared to the Wright brothers’ first plane? How much of the solar power hitting the Earth can we effectively use?

I point you to a paper called Pulling Back The Curtain On The Energy Transition Tale, which I link to in the notes. It’s not peer-reviewed, but shares all its sources. It looks at the limitations of renewable energy sources. What does it take to build solar and wind farms? How many do we have to build? How many can we? Things like that. I recommend reading it. I’ll share some highlights, or lowlights.

To start off, most, about 80 percent of energy comes fossil fuels directly, like heating iron to make steel. Some processes can use electrical power but not all. They cite sources that generating that 20 percent of electrical power would cost $11 trillion for solar cells, just a small part of over $250 trillion, though it would have to be in the desert since we couldn’t transmit it far from there. We’d need to grow the grid 14 times faster than we are to do it by 2050.

[EDIT: They published a peer-reviewed version of the paper: Through the Eye of a Needle: An Eco-Heterodox Perspective on the Renewable Energy Transition, by Megan K. Seibert and William E. Rees]

That’s still not covering fossil fuel things like heating and container ships. We’d have to build solar and wind farms 3 to 4 times faster than ever every years until 2050. Since they last 15 to 25 years, once finished, we’d have to replace them all.

Making the solar cells and windmills requires steel, cement, concrete, and other materials that require temperatures we so far only get from fossil fuels, so we’d have to keep burning them to create the would-be sustainable renewables, but they aren’t sustainable if they require fossil fuels in perpetuity. They also emit greenhouse gases. The paper goes into more detail about alternatives like biogas that don’t work for other reasons. For one thing, land we use to grow fuel we aren’t growing food with, but we’re projected to need all that food.

Building solar panels requires fossil fuel-burning temperatures. The processes produce toxic by-products and other greenhouse gases besides CO2. They require some rare minerals that may run out and so far have often led to human rights abuses in mining them.

Since they operate a few decades, disposing of them may lead them to be 10 percent of electronic waste. Recycling materials so far use techniques that expose people to toxic waste.

Batteries and other storage require hundreds of times more capacity than we have. “The world’s largest battery manufacturing facility—Tesla’s $5 billion Gigafactory in Nevada—could store only three minutes’ worth of annual U.S. electricity demand in its entire year of production. Fabricating a quantity of batteries that could store even two days’ worth of U.S. electricity demand would require 1,000 years of Gigafactory production.”

The paper goes into more detail about limitations of batteries and other storage worth reading. Any number of its points might be enough to derail renewables.

“Large cranes (used to load and unload cargo, in large construction projects, in mining operations, and more), container and other large ships, airplanes, and medium and heavy duty trucks” may never be able to run on batteries or anything other than fossil fuels.

Wind turbines require magnets that require rare earth metals whose mining produces toxic and radioactive waste. The blades are fiberglass that can’t be recycled or reused. Making the towers requires fossil fuels to make the steel and power the large vehicles to transport them. Installing the towers requires heavy trucks and machinery that batteries can’t power to dig deep and manufacture the materials. Plus they use a lot of cement and concrete, which emit a lot of greenhouse gases.

Technology may overcome some of these problems, but remember, these technologies were supposed to solve the problems of past technologies, which were supposed to handle the problems of technologies before them. The paper doesn’t say it, but each solution seems to require more work than all the ones it replaces. Why should we expect this round to be the last when each before only enlarged the problems? Every indication suggests more problems to come with all the waste to manage, manufacture that doesn’t go away, and raw materials we’ll keep needing, destroying the environment and creating deadly working conditions.

The paper then goes into hydropower, fission, and fusion. Hydro has few places that can be dammed left. Fission would need many more to be built, but they take long times and have big waste management issues. The paper details many problems with fusion that may never be solvable—high operating costs, huge needs for water when many areas humans live in are becoming arid, time to build if ever feasible, and so on.

The paper covers carbon capture and storage, mainly pointing out that no viable schemes exist nor on any remotely useful scale. It covers the social exploitation that has always accompanied mining the materials needed for batteries, magnets, and other material parts of renewables.

It talks about physical limits to potential advances. Most of these fields are mature and the technologies reaching those physical limits. Solar cells can’t produce much more power per area than they are, nor can wind.

While cars and bicycles can run from batteries, large trucks for transportation and construction, planes, and freight ships can’t. Probably whole systems of trains can’t run on renewables or at least would need an expanded grid whose construction would take away from the rest of the economy. All high-speed rail projects in the US run over in cost and time.

As for flying, you’ll get to hear the details from the chief engineer when our conversation emerges from the editing pipeline. My high-level takeaways, though, are that batteries add weight and are near their limits on being able to hold enough energy for a long flight and to deliver power fast enough without overheating. These two properties—holding energy and delivering power fast—tend to be exclusive. If you improve one you lose the other. To fly a heavier plane requires moving slower, but planes can only slow so much. It means fewer people and different plane design, but plane design is a mature field. No one knows any new advances. They’re mostly implementing old ones that the industry didn’t use because it optimized for profitability, not sustainability, before pollution became the issue it did.

I understood from him that currently no technologies allow for flights of the capacity, speed, and distance we now consider normal. If we reached the limits of all technologies, I understood we still couldn’t fly dozens of people thousands of miles. Going from North America to Europe would require stopping over in Greenland or Iceland not to recharge, which would take a long time, but to change planes, which would require lots of extra planes on the ground, which adds costs and pollution to manufacture extra planes.

Meanwhile, the Atlantic would now have a huge bottleneck if we could even fly those distances, build enough planes, and generate enough power to charge them in Greenland and Iceland. How many flights per day could these small islands process? Could we cross the Pacific at all by plane?

I’m not bringing these points up to bring you down. I didn’t make up this research. I learned of it through podcast guest Dave Gardner’s podcast Growthbusters episode Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy and the Green New Deal, featuring Megan Seibert, who explains this research and her views. She’s part of the Real Green New Deal project, which I also link to in the notes.

It seems to me if you have to cross Death Valley, it’s useful to know how much water you need and can bring. If we don’t have enough, nobody wins by starting to cross, knowing we won’t make it.

By contrast, reducing consumption and birth rate require no new technological advances, cost little money and probably save more, and when implemented in voluntary non-coercive ways have improved measures of health, longevity, prosperity, abundance, and stability. Solutions exist, just not the ones we’ve fantasized for generations would work.

Living much simpler lives is beyond possible. Contrary to mainstream beliefs, it means what I believe anyone would call a better life not despite not flying all over the world at whim but because of it. Living as our ancestors did doesn’t mean 30 becomes old age or we lose science. On the contrary, probably more longevity and more meaningful interaction with nature.

Life can be great living sustainably. Our entitlement holds us back, not a physical lack of viability.

More episodes

View all episodes

841. 841: Sandra Goldmark, part 1: Fixation: How to Have Stuff without Breaking the Planet

41:57||Ep. 841How often does something break that you know could be fixed, but you don't know how and there are no places to fix it? I remember repair stores all over the place, but the field doesn't exist any more. We all know about planned obsolescence and how products are designed to break. Now we feel we have to throw things away and replace them (after avoiding buying things when possible, which is far more than most of us practice).Enter Sandra Goldmark, as a member of a growing movement to fix things and make things fixable. She's also an Ivy League professor at Barnard and the Columbia Climate School, so, no, professors don't have to be out of touch.I met Sandra before the pandemic, at a shop she set up down by the South Street Seaport to repair things. Besides her own book Fixation, she was mentioned in a book (The Repair Revolution) in my sustainability leadership workshop alumni book club.Lest you think people have to be born fixers or educated as engineers, a preconception that I find still holds me back, she shares her background not growing up with those things. On the contrary, she found she enjoyed it and found community.Listen for a basic human approach to fixing things and changing culture.Sandra's home pageHer book, FixationHer page at Barnard

840. 840: Dr. Leonardo Trasande, part 1: Sicker, Fatter, Poorer: The Urgent Threat of Hormone-Disrupting Chemicals to Our Health and Future ... and What We Can Do About It

01:10:11||Ep. 840I found Dr. Trasande quoted in a Washington Post article The health risks from plastics almost nobody knows about: Phthalates, chemicals found in plastics, are linked to an array of problems, especially in pregnancy. He said, "Endocrine-disrupting chemicals are one of the biggest global health threats of our time ... And 2 percent of us know about it---but 99 percent of us are affected by it.”The article said that he said that "at the population level, scientists can see telltale signs that those chemicals are undermining human health, adding to growing male infertility or growing cases of ADHD." This outcome suggests a violation of this nation being founded on protecting life, liberty, and property, and the consent of the governed. I also found from this video, Food Contaminants and Additives, that he reported his results thoroughly, taking care not to venture outside his research.I had to talk to him.We talked about his research, what brought him to a new field, now burgeoning, of learning about chemicals that disrupt our endocrine systems---that is, they mess with our hormones. You'll hear that he didn't intend to go into it. It was (tragically) growing in importance since our hormone systems are becoming increasingly disrupted, as are those of many species.I should be more accurate. They aren't passively being disrupted. Consumers are paying companies to produce chemicals that do it.It sounds slimy and scary. I'd rather it didn't happen, but since it does, I'd rather know than not know. I think you would too.Dr. Trasande's NYU faculty page

839. 839: Saabira Chaudhuri: Consumed: Throwaway Plastic Has Corrupted Us

48:34||Ep. 839Reading Saabira's New York Times piece Throwaway Plastic Has Corrupted Us told me she saw more about plastic and its effect on our culture than most. A quote from it: "The social costs of our addiction to disposable plastics are more subtle but significant. Cooking skills have declined. Sit-down family meals are less common. Fast fashion, enabled by synthetic plastic fibers, is encouraging compulsive consumption and waste."Her tenure at the Wall Street Journal told me she would communicate it effectively, pulling no punches. As much as I prefer not to link to social media, this video review by Chris van Tulleken, bestselling author of Ultra-Processed People, is about as positive a review as I've seen, all the more since he clarifies that he doesn't know her.So I invited her to talk about her book Consumed: How Big Brands Got Us Hooked on Plastic. It launches today (October 7) in the US, so I've only finished the beginning, but it delivers. In our conversation, she describes what to expect when you read it, plus her back story driving her to write it.Many reviews describe her humor. You'll hear that I held back from asking her about how she worked humor into the topic, since she's not a comedian so I wouldn't expect to perform unprepared, but no worry, she made me laugh unprompted and shared more humor from the book. Obviously it's a serious topic, and Saabira's work shows how much more serious than you probably thought, but being depressed doesn't help solve it.Saabira's home pageHer New York Times piece that brought me to her: Throwaway Plastic Has Corrupted UsHer book page for ConsumedThe video review we mention by Chris van Tulleken, bestselling author of Ultra-Processed People

838. 838: Zach Rabinor, part 2: What if your business and values clash?

01:01:27||Ep. 838Zach and I got so into our first conversation that we had to take a second one to get to the Spodek Method.Listen for yourself, but I hear Zach working with three motivations:His surfer, outdoors self wants to conserve, protect, and enjoy nature and enable others to do the same by experiencing it.His CEO self wants to deliver what his customers want, despite what they want including polluting and depleting---that is, hurting people and wildlife---beyond what nearly anyone who ever lived has. They don't know it and his company's current message implies that they're helping, not hurting.His leadership self wants to improve himself and his work, to resolve conflict, to explore his boundaries and his team's to see if they can change the world.This situation exists in nearly everyone I know: we love humanity and nature, we live in a culture that rewards the destruction of each, and we want to help resolve that conflict. The difference with Zach is not that the stakes are higher. It's that he is willing to share this internal conflict publicly, not to hide it or act like it isn't there. Only by examining one's blind spots and vulnerabilities can one grow in the areas we care about most. Zach is out on the forefront.

837. 837: Zach Rabinor, part 1: Getting serious about sustainable travel?

01:03:40||Ep. 837I met Zach at an event I spoke at sponsored by the Young Presidents Organization, whose members tend to be successful in business. The criteria to join require it. I knew the people would be friendly, but suspected they would pollute and deplete more than most without realizing it.Zach plays a leadership role in the local chapter and was one of the organizers for this event so we interacted more. He was open and sincere about learning about my work and sustainability leadership. As you'll hear, he runs a business that pollutes and depletes---that is, hurts people and wildlife---a lot. Like nearly all businesses that do, it portrays itself as clean and helping people stay clean while doing things that pollute and deplete.Not many people face their inner conflicts, let alone voice them publicly. I see no other way to resolve them. No one has solved the challenges Zach is choosing to face. I know they can be solved as does he, I suspect, but getting there will be hard. Restoring sustainability to his business, among the most polluting and depleting, will be hard, mostly people and cultural challenges, not technical or legislative.I see Zach as a potential pioneer. Let's see if we can help him achieve what few others are trying and most are just covering up.

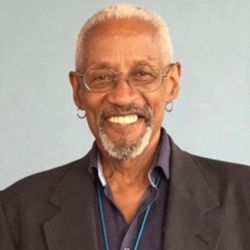

836. 836 Dr. Robert Fullilove, part 5: Unsustainability is upstream of imperialism, colonialism, slavery, and racism

01:34:47||Ep. 836Since our fourth recording, Dr. Bob and I spoke at length about what's driving me and keeping me going beyond where nearly anyone else does on sustainability leadership. We cover in this recording most of that conversation, plus we go in other directions.He shares the commonalities of what he sees in me and my work with the people he's known and worked with who are also working or worked to change the world, including Martin Luther King, Stokely Carmichael, John Lewis, and his wife, Mindy Fullilove. In the process, I end up sharing parts of my upcoming book. His experience with them, as well as working with prisoners and his experience with psychology and social work, gave me space to open up about racism and my past.This episode felt personal to me. Normally I try to showcase the guest, but his experience and demeanor ended up mentoring me. I felt like I got more out of the conversation than he did, but he said he loved it.This episode differs from most on this podcast. I suspect you'll like its openness, previews of my next book, and his warmth.

835. 835: At last! I can access my roof to charge solar for the first time in 18 months.

30:21||Ep. 835This week, I charged my solar panel and battery on my roof for the first time for over 18 months. My building had to do maintenance during which no residents could access the roof. They told us the job would take 5 months, but it took over 18. They also didn't say exactly when it would start until one day I got an email that said I couldn't access the roof until they finished the job.What a relief! This episode shares some of my experiences. Some I liked, like that it helped me develop resilience, it saved me more money, it led to my food being fresher, and it led me to connect with people ranging from local residents to indigenous people around the world to people who lived without electrical power in the past, which is all your ancestors up to the most recent few.

834. 834: Do Americans Know How to Prepare Food From Scratch?

14:10||Ep. 834Late summer means produce at peak ripeness, especially peaches and heirloom tomatoes. Regular readers of my blog and subscribers to my newsletter have read of how my volunteering to bring overstock food from stores to places that give it to anyone for free has led to my getting for free amounts I can barely keep up eating that people turn down.This episode shares a saga of my confusion and exasperation at people throwing away and not accepting perfectly good food. I don't want to take it but the alternative is to throw it away.While it's tragic that poor people don't accept this bounty of nature and our broken food system, I'm concluding a bigger picture. I think a large fraction of Americans don't know what to do with fresh, unpackaged produce. They know how to eat apples and bananas. Even other fruit, let alone vegetables like zucchini or radishes, I think they don't know what to do with. I mean, you can pick up a tomato and eat it, and heirloom tomatoes have so much flavor, eating them is like eating gazpacho. Well, the flavor is subtle, so if you're used to doof like Doritos and Ben and Jerry's, you won't notice their nuance and complexity, but still, eating them takes no skill.A couple recent blog posts on the topic:When did you last prepare a full meal from scratch, not one packaged product?More fresh juicy local peaches and heirloom tomatoes than I can handle, saved from waste by rich and poor alike

833. 833: Aaron Blaise: A Master Disney Director and Animator on Self Expression, Leadership, and Nature

01:06:47||Ep. 833Aaron and I met after I got to see a screening of his recent short animated film Snow Bear. I knew about Aaron's achievements from participating in some of the biggest animated movies of all time. I expected to talk about art, creativity, and expression, topics I love. We did, after first hitting on leadership, especially empathy.He started by sharing his growth as an animator and director at Disney. Soon enough we dove into talking about the overlap between leadership and things he loved about his career: directing, teamwork, self-expression, and empathy. We talked about being generous, what it takes to get the best out of a team, and how it feels when you do. We distinguished leadership from authority and how many people confuse them.You'll hear we both enjoyed the richness and depth of our exploration of similar passions from different directions. Plus you'll hear the back story Snow Bear that gives it its richness and depth.Aaron's web page