Share

This Sustainable Life

471: 12 Sustainability Leadership Lessons Unplugging My Fridge for 6.5 Months Taught Me

Isn’t a refrigerator essential? Isn’t life with them better?

I thought so. I’ll quote my mom from my podcast to illustrate where I came from:

I grew up where it was easily ninety degrees every single day. In fact, where I worked, the store if it got ninety degrees outside we got to close the store and go home because it was that unsafe. To me, air conditioning was wonderful. And to my mom and my grandmother, not having to use ice box refrigerators was great. I really appreciate all of that today and I understand that we’ve gone overboard with air conditioning. It’s really bad for the environment and one should learn how to get along with these temperatures.But Josh, it was really hot in South Dakota. Unless you had really, really good screens, when you opened the windows you were covered with mosquito bites. I don’t want to revisit that at all ever. I am willing to use fans and cut out a lot of air conditioning but to me it means giving up a lot that made my life a lot better.I didn’t have much but what I had was good. It seems to me like you’re asking me—not you personally—but we’re saying stop doing these things that brought joy. I’m not excessive.Her experience is no air conditioning bad, air conditioning good. No fridge bad, fridge good. Most of us share the experience and belief. It’s our culture. As long as we don’t challenge our beliefs and culture, we’re stuck polluting. We’ll keep sleepwalking into an uninhabitable Earth.

But people lived without refrigeration for hundreds of thousands of years. Were they all miserable all the time? Other cultures always look odd until we get them.

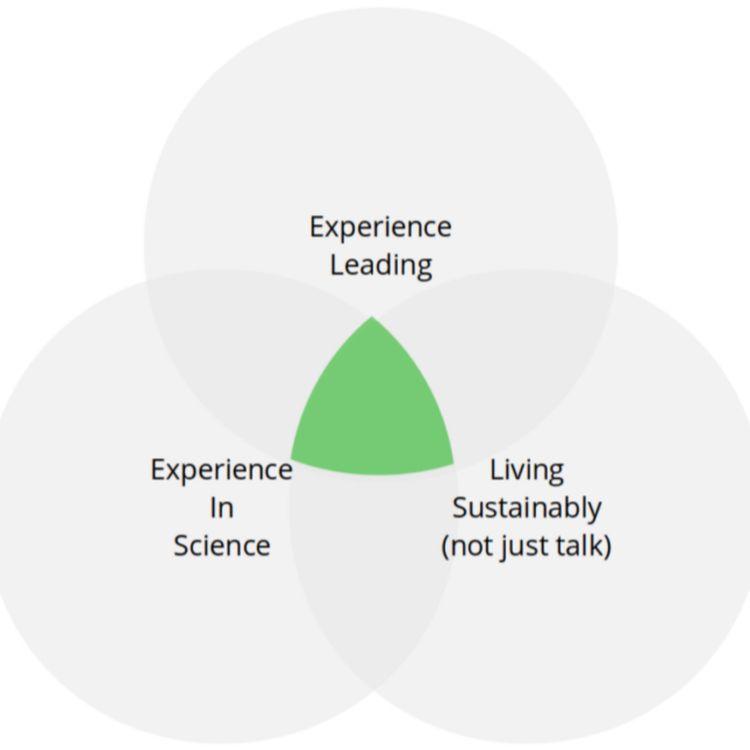

Changing Culture from Polluting to StewardingTo change American and global culture to embrace stewardship and pollute less, not thinking it means deprivation, sacrifice, burden, and chore, but joy, fun, freedom, connection, community, meaning, and purpose, a leader needs experience in three areas:

- Leading people

- Science

- Living the values he or she proposes others adopt

Most people have one or two. I know of almost no one with all three. Many scientists, educators, and journalists know science, but not how to lead. They spread facts, figures, and instruction, where rarely lead people to change. Many leaders don’t know science so they promote ideas that sound nice but don’t work.

Even among people who lead and know science—a rare combination—few to none have tried to live sustainably. Sadly and unintentionally, they present solutions as abstract at best, more often as something even they don’t want but we have to.

I’ve Been to the Mountain Top and Seen the Promised LandI don’t avoid packaged food and flying to deprive myself, nor because I believe my contributions divided by 7.8 billion round off to more than zero. I do it on a personal level to live by my values and not pollute. But from a sustainability leadership perspective, I do it to learn what living sustainably means and what the transition requires.

Changing a lifestyle isn’t a matter of new technology or instruction. It takes new role models, beliefs, stories, images, support, community, and things like that. The challenge of building muscle at the gym isn’t know what weights to lift. It’s how to go when you don’t feel like it or your friends discourage you, handling injuries or slow progress, diet, sleep, great coaching, and so on.

In Martin Luther King speak, to reach the promised land, you have to climb the mountain, which few people want to do first. They don’t see the value. Someone has to go first and show it can be done. A few will follow. Then it becomes mainstream.

Why I Unplugged My FridgeI recorded a podcast episode that goes into more depth, but the biggest reason I tried the experiment is that renewable power sources are intermittent. Could I live so if the power went down I didn’t suffer? Making grids have more uptime costs money, reduces energy security, and requires highly polluting peaker plants and nuclear.

We’re on a treadmill of every time we enable our grid to provide more power and uptime, we use it all up. We started browning out power grids with air conditioning in the 1940s. Since then we built them to much greater capacity, but we see brownouts as much as ever. We keep making ourselves dependent at tremendous cost and insecurity for marginal benefit. That’s our choice.

What if we made ourselves resilient? What if, like most of the world, we could handle the power going down more? We’d save money, increase energy security, and could get by with only renewables, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Renewable Electricity Futures Study.

Imagine! We could live on only solar and wind by spending less money. A major hurdle is refrigerators. Making our culture resilient to them could save us money, make us resilient, and enable us to switch to renewables. Can we live in the modern world without them?

Before I unplugged mine the first time, in December 2019, I doubted I could make it a day or two. I made it three months! The next time I tried, last November, I made it over six and a half months!

What I learned Living Without a Fridge for Six and a Half Months- Face problem, then solve it. Don’t try to solve it in the abstract. It’s easier to figure out how to preserve food when your food is going to go bad if you don’t than to imagine what you’d do hypothetically. Then your imagination comes up with more possibilities than would arise, paralyzing you from acting.

- We connect with other cuisines more by living in our own culture than visiting others. February and March in New York mean parsnips, beets, potatoes, and mostly root vegetables plus the greens I fermented or sprouted. What sounds subtractive actually makes the process constructive and creative. How do I make what I have taste good? This restriction connects me more with other cultures because their cuisines emerged from that constraint. We may use different vegetables, but we connect culturally. Now I see visiting another culture for a weekend or even a few months more like visiting a zoo. We also undermine our own culture. Most tourist places have restaurants from everywhere. We’re turning once-unique cultures into a global mesh with decreasing distinction. Cooking local moves in the other direction.

- Less tech means more connection. Less technology forces me to learn what to do from family, friends, and people with similar goals, like authors and people who make videos. This exercise connected me with people. It revealed that technology generally separates us more than connects us. Of course, exceptions exist.

- Fermentation and sprouting are easy and fun. Before this experience, fermentation sounded scary, dangerous, and hard. I didn’t think about sprouting at all. Now I see fermentation as how civilization began and quick and easy, producing rich and complex flavors. I can do it simply now, basically chopping vegetables, adding salt, mixing them, and putting them in a jar. I started with sauerkraut and vinegar and moved to chutneys, kvass, and fermenting random vegetables and fruit to keep them edible. Bean sprouts took less time and effort at pennies a pound.

- The exercise was about resilience more than power. Few things are more repellent than neediness and entitlement. Do you know anyone you like more for their neediness? Well, needing a fridge is needy. Our technologies are supposed to make us more capable but are making us more dependent and needy.

- Whole fruits and vegetables last longer than I expected. Before this exercise, I thought packaging extended the lives of things, but fruits and vegetables, especially root vegetables, stay fresh a long time. Cabbage, beets, potatoes, and winter vegetables can stay fresh weeks to months without special treatment, longer with fermentation. A lot of packaged stuff starts going bad soon after opening. Some of it never decomposes because it contains no nutrition to attract microbiota that would eat it.

- Living by a value anew makes me want to solve more, like going off-grid. Since I started by thinking this challenge was beyond my abilities, I considered it a goal, and a stretch at that. As the weather warmed, I expected every week to be as far as I could go. Then March led to April. I kept expanding my skills to ferment and keep things fresh otherwise, which led to May, which led to June. The more I learned the more I saw I could do more. For example, seeing monthly electric charges on my bill of $1.70, $1.70, and $1.40 got me wondering how low I could go. Could I go off the electric grid for months at a time? I don’t yet know, but the question prompted me to start researching and experimenting with living on solar. I’m seeing if I can disconnect from Con Ed next time. Stay tuned.

- We’re freaking spoiled and entitled. American culture and the cultures of most peer countries make us dependent, spoiled, and entitled, insensitive and dismissive of people we know we’re hurting. Most people who are spoiled and entitled don’t know it. No one said no to them and they prefer keeping it that way. But I think we all know they’d prefer not to be spoiled if they knew. We are spoiled. We don’t want anyone denying us our fleeting indulgences either, but expand our horizons and we’ll stop being so entitled. In the middle of my experiment, the New York Times posted When One Fridge Is Not Enough, which started: “For many Americans, a second fridge—and sometimes a third—is another member of the family” with pictures of giant refrigerators filled with expensive, unhealthy, needless doof. Member of the family? What happened to us?

- Everyone wants to protect elderly and helpless, not thinking through that you can adjust for them. Common first reactions to hearing what I’m doing begin with, “You can do it because you’re privileged,” though not with questions to learn if I am or not. Something about me leads people to conclude that I must be privileged and out of touch with the lives of others. In any case, of course people range in their dependence on refrigerators and other technology. That some people need more doesn’t mean we can’t change for everyone else, nor should it stop us from thinking and discussing the possibilities.

- Freedom is opposite of neediness. The more I needed a fridge, the less freedom I had. I don’t mean political freedom. I mean mental, emotional, and physical freedom. Needing a fridge means dependence. Not needing one opens the world to where and what I can eat.

- The key word in “dependence on foreign oil” isn’t ‘foreign.’ It’s ‘dependence.’ Pundits talks about our dependence on foreign oil as if needing it from another country makes America unstable. On the contrary, the dependence is the main problem. Wherever it comes from, neediness means people can control us. When has desperation improved your life?

- Sustainability isn’t a goal or target but skills that once you start you find more. Speaking of commitments to pollute less, I picked up the following pattern from my podcast guests: guests who had already acted in stewardship the most tended to come up fastest with new things they could do. People who hadn’t done much tended to give up or push back. They’d say they already drove an electric car and avoided bottled water, ask (rhetorically) what more could they do, and declare themselves one of the good guys and stop thinking about it.

Future generations will recoil in horror at our choosing comfort and convenience that contributes to ten thousand years of degrading Earth’s ability to sustain life. We wantonly create suffering by compartmentalizing activities we think will improve our lives from the pollution they cause.

I’m describing a social, emotional problem. Technology rarely solves social and emotional problems Solving our social and emotional problems will not likely come from more tech. More often it will come from less, which helps us learn our values and act on them.

Learn Resilience Like Learning to Raise a ChildHow does one learn to raise a child?

You can learn all you want before the child is born, but giving birth is where the learning begins. All the hypothetical becomes real and counts.

If we want to lower emissions, building more solar and wind is nice. I’m glad we’re doing it, but we’re using more than we need. Shutting down fossil fuel-based energy will transition us faster. Of course, plan for the helpless so their lights don’t go out. But face the problem to solve it. Analyzing and planning more than we have keep delaying and confusing. Let’s give birth to the baby. When we face actual problems, entrepreneurs will innovate the solutions to them. Not economists publishing papers on their imaginations. Create new markets. Use different metrics than GDP.

Baker’s DozenHere’s a baker’s dozen lesson 13. Turning on fridge felt gross. I plugged it in at last because today hit 90F (32C) and yesterday began my summer CSA, meaning many fresh leafy greens that would wilt in the heat.

I unplugged it November 22, expecting to last to March and made it to June instead. Next time I’ll start earlier to get month or two extra. Maybe October or September. Maybe I’ll try sooner.

More episodes

View all episodes

846. 846: Gail Eisnitz: The Inside Story of a Life Investigating Factory Farms

01:00:13||Ep. 846Gail shares her investigations into meat industry practices, exploring how exorbitant slaughterhouse production line speeds in a consolidated slaughter industry affect animals as they are being handled and killed, and how the proliferation of massive factory farms impacts animals being raised in intensive confinement.She spent decades in the field documenting violations against farm animals and in the office preparing cases and writing about her investigations in articles and books. Her efforts to expose and prosecute animal abusers were often thwarted by network television producers and by law enforcement authorities. Producers considered her findings too disturbing. The law refused to prosecute abusers. Instead they provided cover for the meat industry---a billion-dollar industry.She gives an inside view behind the closed doors of U.S. slaughterhouses and factory farms. She also shared her challenges and successes in documenting and exposing the findings.As a memoir, Out of Sight has been described by reviewers as a “detective story” and a “page turner” that they “can’t put down," probably for her personal challenges related to her diagnosis with a rare medical visual condition she shares in our conversation.Gail's web pageThe Humane Farming AssociationHer most recent book: Out of Sight An Undercover Investigator's Fight for Animal Rights and Her Own SurvivalHer first book: Slaughterhouse The Shocking Story of Greed, Neglect, and Inhumane Treatment Inside the U.S. Meat Industry

845. 845: Sarah Goodyear and Doug Gordon: The War on Cars and Life After Cars

01:26:50||Ep. 845Doug and Sarah's podcastThe War on Cars is a podcast that delivers news and commentary on the latest developments in the worldwide fight to undo a century’s worth of damage wrought by the automobile, approaching the topic from all angles, from politics to pop culture. They release two regular episodes and one Patreon bonus episode per month.Doug and Sarah's BookCars ruin everything. That’s why we need Life After Cars.When the very first cars rolled off production lines, they were a technological marvel, predicted to make life easier and better for everyone; yet a hundred years later, that dream is running on empty.Instead of unbounded freedom, the never-ending proliferation of automobiles has delivered a host of costs, among them the demolition of our neighborhoods, towns, and cities to make way for car infrastructure; an epidemic of violent death; countless hours lost in traffic; isolation from our fellow human beings; and the ongoing destruction of the natural world.That’s why we need Life After Cars. Through historical records, revealing interviews, and unflinching statistics, Sarah Goodyear and Doug Gordon, hosts of the podcast The War on Cars, and former host Aaron Naparstek unpack the scale of damage that cars cause, the forces that have created our current crisis and are invested in perpetuating it, and the way that the fight for better transportation is deeply linked to the fight for a more equitable and just society.Life After Cars expands on the podcast with new interviews and original content—offering something for everyone, from longtime listeners familiar with the harms of car culture to those just beginning to imagine a world with fewer metal boxes zooming around.Cars as we know them today are unsustainable—but there is hope. Life After Cars will arm readers with the tools they need to implement real, transformative change, from simply raising awareness to taking a stand at public forums.It’s past time to radically rethink—and shrink—society’s collective relationship with the automobile.The podcast: The War on CarsThe book: Life After Cars

844. 844: Maya Lilly, part 1: Effective Storytelling and Producing The Years Project

01:35:59||Ep. 844Since I've seen Maya's work on the Years Project with people like executive producers James Cameron and Arnold Schwarzenegger, I was worried I might feel starstruck.Oh wait, she also worked with series creators Joel Bach and David Gelber (of 60 Minutes); chief science advisors podcast guest Joseph Romm and Heidi Cullen; and episode hosts including Cameron, Schwarzenegger, Harrison Ford, Ian Somerhalder, America Ferrera, David Letterman, Gisele Bündchen, Jack Black, Matt Damon, Jessica Alba, Sigourney Weaver.Oh, and the series won an Emmy for Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Series.She was engaging, informative, open, and fun. We laughed a bunch We talked about her passion for the art and practice of storytelling. You have to be true to the science, but you can't skimp on the story or take for granted it will work. We also talked about her background that brought her to this level.The Years ProjectIts YouTube pageMaya's curated climate listUPDATE: After we recorded, Maya noted that about halfway in, she said "Bread and Puppet theatre in San Francisco." The actual troop was The San Francisco Mime Troupe.

843. 843: Judith Enck, part 2: The Problem with Plastic (the Book)

28:43||Ep. 843Judith just published The Problem with Plastic: How We Can Save Ourselves and Our Planet Before It’s Too Late.I've read a lot about plastic and hosted many authors. I won't lie. Before starting the book, I thought I should read it because I knew her, but didn't expect much.Instead, I learned a lot new. I found it engaging and compelling. I recommend it.Yes, you'll learn things that are sobering, but you'd rather know than not know, especially things that affect your health and safety and your family's. It also guides you to how to respond, personally, socially, and politically. Judith cares and has experience.Start by listening to our conversation. Then read the book.The Problem with Plastic: How We Can Save Ourselves and Our Planet Before It’s Too LateWEBINAR with co-authors Judith Enck, Adam Mahoney, and Melissa Valliant, January 28, 2026

842. 842: Silvia Bellezza, part 1.5 and 2: When at first you don't succeed

39:44||Ep. 842Since Silvia teaches as a business school, I'll address a leadership aspect of our interaction. I skimped on a leadership step, so we did an episode 1.5, which is my lingo for redoing episode 1 when the person wasn't able to fulfill his or her commitment. That's my responsibility as leader of the interaction.Silvia and I had a wonderful first conversation that led to a commitment that sounded like she'd enjoy it and doable, but in the end wasn't quite. Even if a quick hike north of the city would be enjoyable, catching a Metro-North train from Columbia University isn't that convenient and her schedule may not have bee as flexible as she suspected in our first conversation.For those listening to these conversations to learn the Spodek Method, in our first conversation I didn't check with her how practical the commitment was given her constraints. As the leader of the interaction, I should have asked ahead to imagine her schedule, the logistics of catching the train, and so on. The key measure the first time someone acts on their intrinsic motivation isn't how big it is. It's if they person does it.When someone acts on intrinsic motivation, they'll find it rewarding. If they feel reward, they'll want to do it again and the next time will be bigger, especially if they've always considered acting on sustainability a sacrifice or something that has to be big or any of the other myths people propagate. Sadly, even ardent environmentalists lead people to think of acting more sustainably as something they won't like or won't find rewarding when they use tactics like trying to convince, cajole, coerce, or seek compliance.In this double episode we hear how she did something more practical. At the end, note that she's open to doing more.

841. 841: Sandra Goldmark, part 1: Fixation: How to Have Stuff without Breaking the Planet

41:57||Ep. 841How often does something break that you know could be fixed, but you don't know how and there are no places to fix it? I remember repair stores all over the place, but the field doesn't exist any more. We all know about planned obsolescence and how products are designed to break. Now we feel we have to throw things away and replace them (after avoiding buying things when possible, which is far more than most of us practice).Enter Sandra Goldmark, as a member of a growing movement to fix things and make things fixable. She's also an Ivy League professor at Barnard and the Columbia Climate School, so, no, professors don't have to be out of touch.I met Sandra before the pandemic, at a shop she set up down by the South Street Seaport to repair things. Besides her own book Fixation, she was mentioned in a book (The Repair Revolution) in my sustainability leadership workshop alumni book club.Lest you think people have to be born fixers or educated as engineers, a preconception that I find still holds me back, she shares her background not growing up with those things. On the contrary, she found she enjoyed it and found community.Listen for a basic human approach to fixing things and changing culture.Sandra's home pageHer book, FixationHer page at Barnard

840. 840: Dr. Leonardo Trasande, part 1: Sicker, Fatter, Poorer: The Urgent Threat of Hormone-Disrupting Chemicals to Our Health and Future ... and What We Can Do About It

01:10:11||Ep. 840I found Dr. Trasande quoted in a Washington Post article The health risks from plastics almost nobody knows about: Phthalates, chemicals found in plastics, are linked to an array of problems, especially in pregnancy. He said, "Endocrine-disrupting chemicals are one of the biggest global health threats of our time ... And 2 percent of us know about it---but 99 percent of us are affected by it.”The article said that he said that "at the population level, scientists can see telltale signs that those chemicals are undermining human health, adding to growing male infertility or growing cases of ADHD." This outcome suggests a violation of this nation being founded on protecting life, liberty, and property, and the consent of the governed. I also found from this video, Food Contaminants and Additives, that he reported his results thoroughly, taking care not to venture outside his research.I had to talk to him.We talked about his research, what brought him to a new field, now burgeoning, of learning about chemicals that disrupt our endocrine systems---that is, they mess with our hormones. You'll hear that he didn't intend to go into it. It was (tragically) growing in importance since our hormone systems are becoming increasingly disrupted, as are those of many species.I should be more accurate. They aren't passively being disrupted. Consumers are paying companies to produce chemicals that do it.It sounds slimy and scary. I'd rather it didn't happen, but since it does, I'd rather know than not know. I think you would too.Dr. Trasande's NYU faculty page

839. 839: Saabira Chaudhuri: Consumed: Throwaway Plastic Has Corrupted Us

48:34||Ep. 839Reading Saabira's New York Times piece Throwaway Plastic Has Corrupted Us told me she saw more about plastic and its effect on our culture than most. A quote from it: "The social costs of our addiction to disposable plastics are more subtle but significant. Cooking skills have declined. Sit-down family meals are less common. Fast fashion, enabled by synthetic plastic fibers, is encouraging compulsive consumption and waste."Her tenure at the Wall Street Journal told me she would communicate it effectively, pulling no punches. As much as I prefer not to link to social media, this video review by Chris van Tulleken, bestselling author of Ultra-Processed People, is about as positive a review as I've seen, all the more since he clarifies that he doesn't know her.So I invited her to talk about her book Consumed: How Big Brands Got Us Hooked on Plastic. It launches today (October 7) in the US, so I've only finished the beginning, but it delivers. In our conversation, she describes what to expect when you read it, plus her back story driving her to write it.Many reviews describe her humor. You'll hear that I held back from asking her about how she worked humor into the topic, since she's not a comedian so I wouldn't expect to perform unprepared, but no worry, she made me laugh unprompted and shared more humor from the book. Obviously it's a serious topic, and Saabira's work shows how much more serious than you probably thought, but being depressed doesn't help solve it.Saabira's home pageHer New York Times piece that brought me to her: Throwaway Plastic Has Corrupted UsHer book page for ConsumedThe video review we mention by Chris van Tulleken, bestselling author of Ultra-Processed People

838. 838: Zach Rabinor, part 2: What if your business and values clash?

01:01:27||Ep. 838Zach and I got so into our first conversation that we had to take a second one to get to the Spodek Method.Listen for yourself, but I hear Zach working with three motivations:His surfer, outdoors self wants to conserve, protect, and enjoy nature and enable others to do the same by experiencing it.His CEO self wants to deliver what his customers want, despite what they want including polluting and depleting---that is, hurting people and wildlife---beyond what nearly anyone who ever lived has. They don't know it and his company's current message implies that they're helping, not hurting.His leadership self wants to improve himself and his work, to resolve conflict, to explore his boundaries and his team's to see if they can change the world.This situation exists in nearly everyone I know: we love humanity and nature, we live in a culture that rewards the destruction of each, and we want to help resolve that conflict. The difference with Zach is not that the stakes are higher. It's that he is willing to share this internal conflict publicly, not to hide it or act like it isn't there. Only by examining one's blind spots and vulnerabilities can one grow in the areas we care about most. Zach is out on the forefront.