Share

This Sustainable Life

063: Technology won’t solve environmental issues and you know it

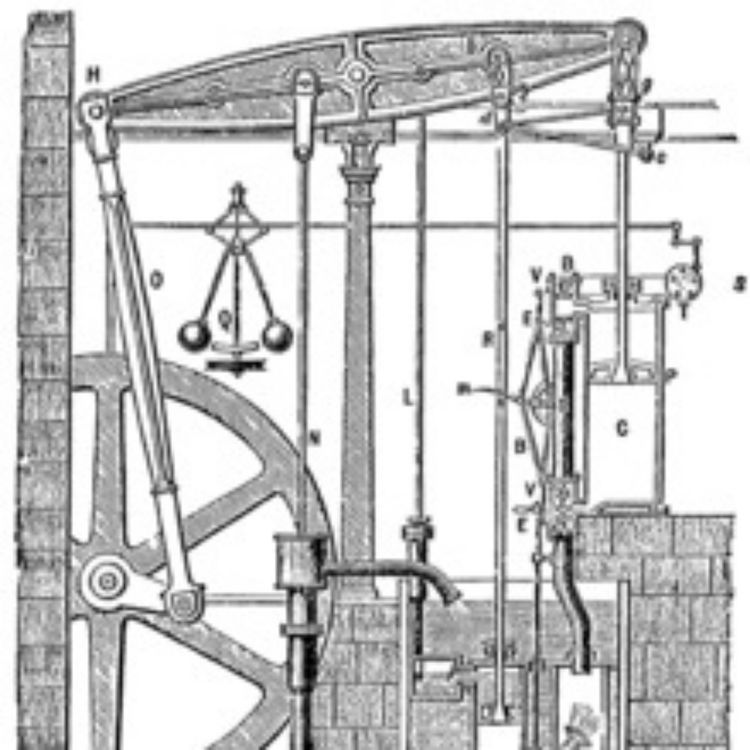

If anything marked the beginning of the industrial revolution, it was James Watt’s steam engine. It wasn’t the first steam engine, but was more efficient than any before.

More efficient means using less energy and less pollution, right?

Wrong.

Each engine, yes, but more people used engines, so Watt engines used more energy and polluted more than anything. They drained mines, which helped collect more coal, which fed more engines.

The direct result is today’s polluted world. If you fantasize that technological improvements will, after centuries since the industrial revolution increasing pollution and demand for natural resources somehow, magically, in your lifetime change their effects, you’re dreaming.

Two main effects drive this pattern—obvious when you see them, however counterintuitive at first. People believe self-serving myths in the opposite direction of millennia of countervailing evidence, probably because they prefer comfort and convenience over the guilt that would come from conscious awareness of how they’re hurting other people. We know the polluted world we were born into. We know the pollution we’re causing—that is, unless we keep lowering our self-awareness with myths.

When costs drop, people use more. For example:

- LEDs are more efficient than incandescents and now people light things they didn’t—by more than the energy saved.

- Gas engines are more efficient today than decades ago and people make cars bigger, heavier, and faster—so mileage is lower than many cars from half a century ago.

A similar effect: building more lands and roads creates more traffic. People already project that autonomous vehicles will increase traffic too.

If you think electric cars, solar power, nuclear power, a hyperloop train system, etc will lower pollution, you’re ignoring history.

Steam engines, LED bulbs, nuclear reactors, and technology in general are elements of a system. Even the whole economy is an element of a global system including the environment and other human systems.

The goals of this overall system have long included growth and individual comfort and convenience. As long as those goals remain, technological innovation will drive them over competing considerations such as conservation and community.

We took generations to learn that building more roads increased traffic, congestion, pollution, time lost, and so on. In that time we locked in infrastructure parts of which will endure centuries, increasing traffic, congestion, pollution, time lost, and so on.

As long as we hold on to these myths that solar planes or whatever will lower overall pollution, we’re locking in more damage.

If you think, “Technology may have increased pollution since the steam engine and before, but this time it will be different,” then you see that we have to change just applying technology as we used to.

You know that for a different result we have to do things differently. Efficiency alone won’t reduce pollution and will likely increase it.

We don’t have to work within the system. We can work on it.

Instead of making the existing polluting system more efficient, we can change the system. That’s the point of my Leadership and the Environment podcast. Leaders change systems. Some do, anyway.

Steam engines, LED bulbs, nuclear reactors, and technology in general affect parts of this system but they don’t change it overall.

Changing the beliefs and goals of a system change it. I’m trying to help people change their beliefs and goals—not just anyone but influential people that many follow. If we don’t change the most influential people then people will keep following them and not adopt new beliefs and goals.

Christianity was more merciful than many systems before it.

Buddhism was more compassionate.

The Enlightenment more observation-based.

Science more skeptical.

We’ve changed systemic goals many times.

We can change from growth—always wanting more—to enough, or as I think: loving what you have. When you realize you can’t have everything, you learn to appreciate, celebrate, and love what you have—in my experience more than when you believe the fantasy.

We can change from individual comfort and convenience to responsibility and caring how we affect others. As any parent, pet owner, or team member will tell you, taking others into account and caring how you affect them increases your compassion, empathy, and overall emotional reward.

More episodes

View all episodes

846. 846: Gail Eisnitz: The Inside Story of a Life Investigating Factory Farms

01:00:13||Ep. 846Gail shares her investigations into meat industry practices, exploring how exorbitant slaughterhouse production line speeds in a consolidated slaughter industry affect animals as they are being handled and killed, and how the proliferation of massive factory farms impacts animals being raised in intensive confinement.She spent decades in the field documenting violations against farm animals and in the office preparing cases and writing about her investigations in articles and books. Her efforts to expose and prosecute animal abusers were often thwarted by network television producers and by law enforcement authorities. Producers considered her findings too disturbing. The law refused to prosecute abusers. Instead they provided cover for the meat industry---a billion-dollar industry.She gives an inside view behind the closed doors of U.S. slaughterhouses and factory farms. She also shared her challenges and successes in documenting and exposing the findings.As a memoir, Out of Sight has been described by reviewers as a “detective story” and a “page turner” that they “can’t put down," probably for her personal challenges related to her diagnosis with a rare medical visual condition she shares in our conversation.Gail's web pageThe Humane Farming AssociationHer most recent book: Out of Sight An Undercover Investigator's Fight for Animal Rights and Her Own SurvivalHer first book: Slaughterhouse The Shocking Story of Greed, Neglect, and Inhumane Treatment Inside the U.S. Meat Industry

845. 845: Sarah Goodyear and Doug Gordon: The War on Cars and Life After Cars

01:26:50||Ep. 845Doug and Sarah's podcastThe War on Cars is a podcast that delivers news and commentary on the latest developments in the worldwide fight to undo a century’s worth of damage wrought by the automobile, approaching the topic from all angles, from politics to pop culture. They release two regular episodes and one Patreon bonus episode per month.Doug and Sarah's BookCars ruin everything. That’s why we need Life After Cars.When the very first cars rolled off production lines, they were a technological marvel, predicted to make life easier and better for everyone; yet a hundred years later, that dream is running on empty.Instead of unbounded freedom, the never-ending proliferation of automobiles has delivered a host of costs, among them the demolition of our neighborhoods, towns, and cities to make way for car infrastructure; an epidemic of violent death; countless hours lost in traffic; isolation from our fellow human beings; and the ongoing destruction of the natural world.That’s why we need Life After Cars. Through historical records, revealing interviews, and unflinching statistics, Sarah Goodyear and Doug Gordon, hosts of the podcast The War on Cars, and former host Aaron Naparstek unpack the scale of damage that cars cause, the forces that have created our current crisis and are invested in perpetuating it, and the way that the fight for better transportation is deeply linked to the fight for a more equitable and just society.Life After Cars expands on the podcast with new interviews and original content—offering something for everyone, from longtime listeners familiar with the harms of car culture to those just beginning to imagine a world with fewer metal boxes zooming around.Cars as we know them today are unsustainable—but there is hope. Life After Cars will arm readers with the tools they need to implement real, transformative change, from simply raising awareness to taking a stand at public forums.It’s past time to radically rethink—and shrink—society’s collective relationship with the automobile.The podcast: The War on CarsThe book: Life After Cars

844. 844: Maya Lilly, part 1: Effective Storytelling and Producing The Years Project

01:35:59||Ep. 844Since I've seen Maya's work on the Years Project with people like executive producers James Cameron and Arnold Schwarzenegger, I was worried I might feel starstruck.Oh wait, she also worked with series creators Joel Bach and David Gelber (of 60 Minutes); chief science advisors podcast guest Joseph Romm and Heidi Cullen; and episode hosts including Cameron, Schwarzenegger, Harrison Ford, Ian Somerhalder, America Ferrera, David Letterman, Gisele Bündchen, Jack Black, Matt Damon, Jessica Alba, Sigourney Weaver.Oh, and the series won an Emmy for Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Series.She was engaging, informative, open, and fun. We laughed a bunch We talked about her passion for the art and practice of storytelling. You have to be true to the science, but you can't skimp on the story or take for granted it will work. We also talked about her background that brought her to this level.The Years ProjectIts YouTube pageMaya's curated climate listUPDATE: After we recorded, Maya noted that about halfway in, she said "Bread and Puppet theatre in San Francisco." The actual troop was The San Francisco Mime Troupe.

843. 843: Judith Enck, part 2: The Problem with Plastic (the Book)

28:43||Ep. 843Judith just published The Problem with Plastic: How We Can Save Ourselves and Our Planet Before It’s Too Late.I've read a lot about plastic and hosted many authors. I won't lie. Before starting the book, I thought I should read it because I knew her, but didn't expect much.Instead, I learned a lot new. I found it engaging and compelling. I recommend it.Yes, you'll learn things that are sobering, but you'd rather know than not know, especially things that affect your health and safety and your family's. It also guides you to how to respond, personally, socially, and politically. Judith cares and has experience.Start by listening to our conversation. Then read the book.The Problem with Plastic: How We Can Save Ourselves and Our Planet Before It’s Too LateWEBINAR with co-authors Judith Enck, Adam Mahoney, and Melissa Valliant, January 28, 2026

842. 842: Silvia Bellezza, part 1.5 and 2: When at first you don't succeed

39:44||Ep. 842Since Silvia teaches as a business school, I'll address a leadership aspect of our interaction. I skimped on a leadership step, so we did an episode 1.5, which is my lingo for redoing episode 1 when the person wasn't able to fulfill his or her commitment. That's my responsibility as leader of the interaction.Silvia and I had a wonderful first conversation that led to a commitment that sounded like she'd enjoy it and doable, but in the end wasn't quite. Even if a quick hike north of the city would be enjoyable, catching a Metro-North train from Columbia University isn't that convenient and her schedule may not have bee as flexible as she suspected in our first conversation.For those listening to these conversations to learn the Spodek Method, in our first conversation I didn't check with her how practical the commitment was given her constraints. As the leader of the interaction, I should have asked ahead to imagine her schedule, the logistics of catching the train, and so on. The key measure the first time someone acts on their intrinsic motivation isn't how big it is. It's if they person does it.When someone acts on intrinsic motivation, they'll find it rewarding. If they feel reward, they'll want to do it again and the next time will be bigger, especially if they've always considered acting on sustainability a sacrifice or something that has to be big or any of the other myths people propagate. Sadly, even ardent environmentalists lead people to think of acting more sustainably as something they won't like or won't find rewarding when they use tactics like trying to convince, cajole, coerce, or seek compliance.In this double episode we hear how she did something more practical. At the end, note that she's open to doing more.

841. 841: Sandra Goldmark, part 1: Fixation: How to Have Stuff without Breaking the Planet

41:57||Ep. 841How often does something break that you know could be fixed, but you don't know how and there are no places to fix it? I remember repair stores all over the place, but the field doesn't exist any more. We all know about planned obsolescence and how products are designed to break. Now we feel we have to throw things away and replace them (after avoiding buying things when possible, which is far more than most of us practice).Enter Sandra Goldmark, as a member of a growing movement to fix things and make things fixable. She's also an Ivy League professor at Barnard and the Columbia Climate School, so, no, professors don't have to be out of touch.I met Sandra before the pandemic, at a shop she set up down by the South Street Seaport to repair things. Besides her own book Fixation, she was mentioned in a book (The Repair Revolution) in my sustainability leadership workshop alumni book club.Lest you think people have to be born fixers or educated as engineers, a preconception that I find still holds me back, she shares her background not growing up with those things. On the contrary, she found she enjoyed it and found community.Listen for a basic human approach to fixing things and changing culture.Sandra's home pageHer book, FixationHer page at Barnard

840. 840: Dr. Leonardo Trasande, part 1: Sicker, Fatter, Poorer: The Urgent Threat of Hormone-Disrupting Chemicals to Our Health and Future ... and What We Can Do About It

01:10:11||Ep. 840I found Dr. Trasande quoted in a Washington Post article The health risks from plastics almost nobody knows about: Phthalates, chemicals found in plastics, are linked to an array of problems, especially in pregnancy. He said, "Endocrine-disrupting chemicals are one of the biggest global health threats of our time ... And 2 percent of us know about it---but 99 percent of us are affected by it.”The article said that he said that "at the population level, scientists can see telltale signs that those chemicals are undermining human health, adding to growing male infertility or growing cases of ADHD." This outcome suggests a violation of this nation being founded on protecting life, liberty, and property, and the consent of the governed. I also found from this video, Food Contaminants and Additives, that he reported his results thoroughly, taking care not to venture outside his research.I had to talk to him.We talked about his research, what brought him to a new field, now burgeoning, of learning about chemicals that disrupt our endocrine systems---that is, they mess with our hormones. You'll hear that he didn't intend to go into it. It was (tragically) growing in importance since our hormone systems are becoming increasingly disrupted, as are those of many species.I should be more accurate. They aren't passively being disrupted. Consumers are paying companies to produce chemicals that do it.It sounds slimy and scary. I'd rather it didn't happen, but since it does, I'd rather know than not know. I think you would too.Dr. Trasande's NYU faculty page

839. 839: Saabira Chaudhuri: Consumed: Throwaway Plastic Has Corrupted Us

48:34||Ep. 839Reading Saabira's New York Times piece Throwaway Plastic Has Corrupted Us told me she saw more about plastic and its effect on our culture than most. A quote from it: "The social costs of our addiction to disposable plastics are more subtle but significant. Cooking skills have declined. Sit-down family meals are less common. Fast fashion, enabled by synthetic plastic fibers, is encouraging compulsive consumption and waste."Her tenure at the Wall Street Journal told me she would communicate it effectively, pulling no punches. As much as I prefer not to link to social media, this video review by Chris van Tulleken, bestselling author of Ultra-Processed People, is about as positive a review as I've seen, all the more since he clarifies that he doesn't know her.So I invited her to talk about her book Consumed: How Big Brands Got Us Hooked on Plastic. It launches today (October 7) in the US, so I've only finished the beginning, but it delivers. In our conversation, she describes what to expect when you read it, plus her back story driving her to write it.Many reviews describe her humor. You'll hear that I held back from asking her about how she worked humor into the topic, since she's not a comedian so I wouldn't expect to perform unprepared, but no worry, she made me laugh unprompted and shared more humor from the book. Obviously it's a serious topic, and Saabira's work shows how much more serious than you probably thought, but being depressed doesn't help solve it.Saabira's home pageHer New York Times piece that brought me to her: Throwaway Plastic Has Corrupted UsHer book page for ConsumedThe video review we mention by Chris van Tulleken, bestselling author of Ultra-Processed People

838. 838: Zach Rabinor, part 2: What if your business and values clash?

01:01:27||Ep. 838Zach and I got so into our first conversation that we had to take a second one to get to the Spodek Method.Listen for yourself, but I hear Zach working with three motivations:His surfer, outdoors self wants to conserve, protect, and enjoy nature and enable others to do the same by experiencing it.His CEO self wants to deliver what his customers want, despite what they want including polluting and depleting---that is, hurting people and wildlife---beyond what nearly anyone who ever lived has. They don't know it and his company's current message implies that they're helping, not hurting.His leadership self wants to improve himself and his work, to resolve conflict, to explore his boundaries and his team's to see if they can change the world.This situation exists in nearly everyone I know: we love humanity and nature, we live in a culture that rewards the destruction of each, and we want to help resolve that conflict. The difference with Zach is not that the stakes are higher. It's that he is willing to share this internal conflict publicly, not to hide it or act like it isn't there. Only by examining one's blind spots and vulnerabilities can one grow in the areas we care about most. Zach is out on the forefront.