Share

Drum Tower

Introducing Drum Tower

•

Two of The Economist's China correspondents, Alice Su and David Rennie, analyse the stories at the heart of this vast country and examine its influence beyond its borders.

They’ll be joined by our global network of correspondents and expert guests to examine how everything from party politics to business, technology and culture is reshaping China and the world.

For almost seven centuries the beats of China’s most famous drum tower, or gulou, kept people in Beijing to time. The Economist’s latest podcast keeps you up to date every Monday.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter here and for full access to print, digital and audio editions, as well as exclusive live events, subscribe to The Economist at economist.com/drumoffer.

More episodes

View all episodes

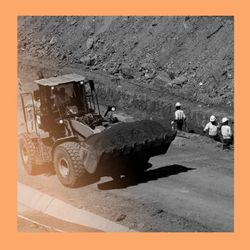

Red dirt: China’s bid to control a new supply chain

32:35|Beneath a ridge in Guinea’s southern highlands lies one of the world's largest deposits of iron ore. Chinese investment has got it out of the ground after decades of delays. But will the Simandou mining project give China the upper hand it hopes?Hosts: Jiehao Chen, The Economist’s China researcher, and Corbin Duncan, our global correspondent.Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+. For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

Secret script: China’s women-only language

31:40|Nushu emerged from the isolated villages of southern China and is the only language created and used exclusively by women. Today it is celebrated across China as a symbol of female empowerment, but the last natural inheritor saw a different meaning. Host: Jiehao Chen, The Economist’s China researcher.Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+. For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

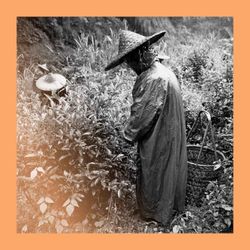

All the tea in China: why Lapsang Souchong is disappearing

27:11|Once a favourite drink of middle-class Brits, Lapsang Souchong is now disappearing from supermarket shelves. We traveled to the remote tea farms of Fujian to find out why. Host: James Miles, The Economist’s China writer-at-large. Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+. For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

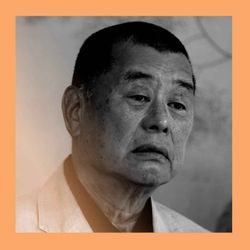

Tycoon troublemaker: the rise and fall of Jimmy Lai

32:43|Media mogul and vocal pro-democracy campaigner Jimmy Lai has been found guilty of conspiring to commit sedition and foreign collusion in a Hong Kong court. Why did the self-made billionaire give up his comfortable life for one of protest—and what does his conviction mean for Hong Kong? Host: Alice Su, The Economist’s senior international correspondent. Guest: Sebastien Lai, democracy activist and the son of Jimmy Lai.Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+. For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

Mama drama: the row over China’s “mum jobs”

24:09|Start later, leave earlier, bring your kids to work. These are some of the perks being offered via “mum jobs”. Local government officials hope they will boost China’s declining birthrates and productivity. So why are they causing uproar among the women they’re supposed to be helping? Hosts: Sarah Wu, The Economist’s China correspondent and our China researcher, Jiehao Chen.You can find The Weekend Intelligence’s Make Babies Great Again episode in their new feed. Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+. For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

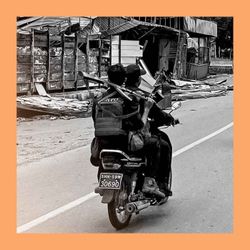

Game of Thrones: China’s ruthless diplomacy in Myanmar

34:53|China says it doesn’t interfere with the affairs of its neighbours, but a leaked transcript suggests that, behind closed doors, diplomats are more than willing to apply the country’s considerable leverage to get what they want.Hosts: Jeremy Page, The Economist’s chief China correspondent and Sue-Lin Wong, our Asia correspondent.You can find out more about Myanmar’s scam compounds by listening to our Scam Inc podcast series. Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+. For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

Trailer: Drum Tower

02:00|Gain a deeper understanding of China with Jeremy Page and Sarah Wu. The Economist’s China correspondents report from across the country and the places it influences beyond its borders. Jiehao Chen joins the discussion from London. This award-winning podcast takes on everything from the CCP to EVs and from ageing to AI. Published every Tuesday.

Grape expectations: Chinese wine may be finer than you think

36:15|In a country better known for Baijiu than Burgundy, the rising popularity of homegrown wine has come as a surprise to some. But production costs are high, while many overseas markets are saturated. Can Chinese wine reach its potential?Hosts: Sarah Wu, The Economist’s China correspondent and Jeremy Page, our chief China correspondent.You can also listen to previous episodes of “Drum Tower” on China’s luxury industries and the decline of alcohol. Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+. For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.

China shock 2.0: why Germany is worried

38:40|As Chinese AI surges ahead, the country’s stranglehold on rare earths tightens and its exports boom, European governments are bracing for a new China shock. Germany is particularly exposed. Is it too late to change its approach? Hosts: Jeremy Page, The Economist’s chief China correspondent, and geopolitics editor David Rennie.Guest: Johannes Volkmann, Christian Democratic Union politician and member of the German Bundestag. Transcripts of our podcasts are available via economist.com/podcasts.Listen to what matters most, from global politics and business to science and technology—subscribe to Economist Podcasts+. For more information about how to access Economist Podcasts+, please visit our FAQs page or watch our video explaining how to link your account.